Entry into Virgil Abloh’s mid-career retrospective, “Figures of Speech,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago begins with a calculated provocation: tourist or purist? According to the catalog foreword written by the exhibition’s curator, Michael Darling, the dichotomy signifies the artist’s split personality— connoisseur and aspirant—and serves as a welcome mat for all audiences to participate in a cultural flashpoint where style destabilizes class (note: the exhibition is aptly dedicated to the youth of Chicago). From this outset, the exhibition tone aims for egalitarianism.

To arrive at this seemingly accessible provocation, however, requires the observer to first pass through a retinal barrage. The exhibition’s lobby includes a floor-to-ceiling collage of images as far ranging as the epileptic singer Ian Curtis to the 9/11 WTC bombings—recalling OMA/AMO’s 2004 book-zine monograph, Content—and serves as fast entry into the artist’s ever-expanding cult of cultural clashes. It comes as no surprise that Samir Bantal, Director of AMO, is credited as the exhibition’s designer. In addition to an equally satisfying collage pitting images of Le Corbusier over ARCHITECTURE and Abloh over “ARCHITECT,” one is subsumed into the allure of a retail pop-up store, titled “Church and State,” offering limited Off-WhiteTM clothing, gradient furniture, and exhibition catalogs immersed within a life-size wallpaper photo-essay by the German photographer Juergen Teller. And don’t worry if you can’t afford the catalog, there’s also a free copy machine on site. Yet, for the public to even arrive at this exquisite amalgamation of gallery-cum-shop-cum-academy-cum…, means also visiting an outbreak of satellite ventures c/o Abloh across the city that include the NikeLab Chicago Re-Creation Center, where old sneakers can be donated and ground into a reusable architectural finish, or a temporary Louis Vuitton residency in an orange painted building within which stands a David-sized mannequin of the rapper Juice Wrld. So, to reset: the exhibition does not actually start in the lobby of the Museum of Contemporary Art, but rather, on the streets of Chicago. Even the museum’s Mies van der Rohe Way façade has been rebranded with “CITY HALL” and a black flag that breathes “QUESTION EVERYTHING” in white Helvetica lettering. Fifteen years later, Abloh and Bantal appear to have manifested Content’s flat ambition into something truly three-dimensional.

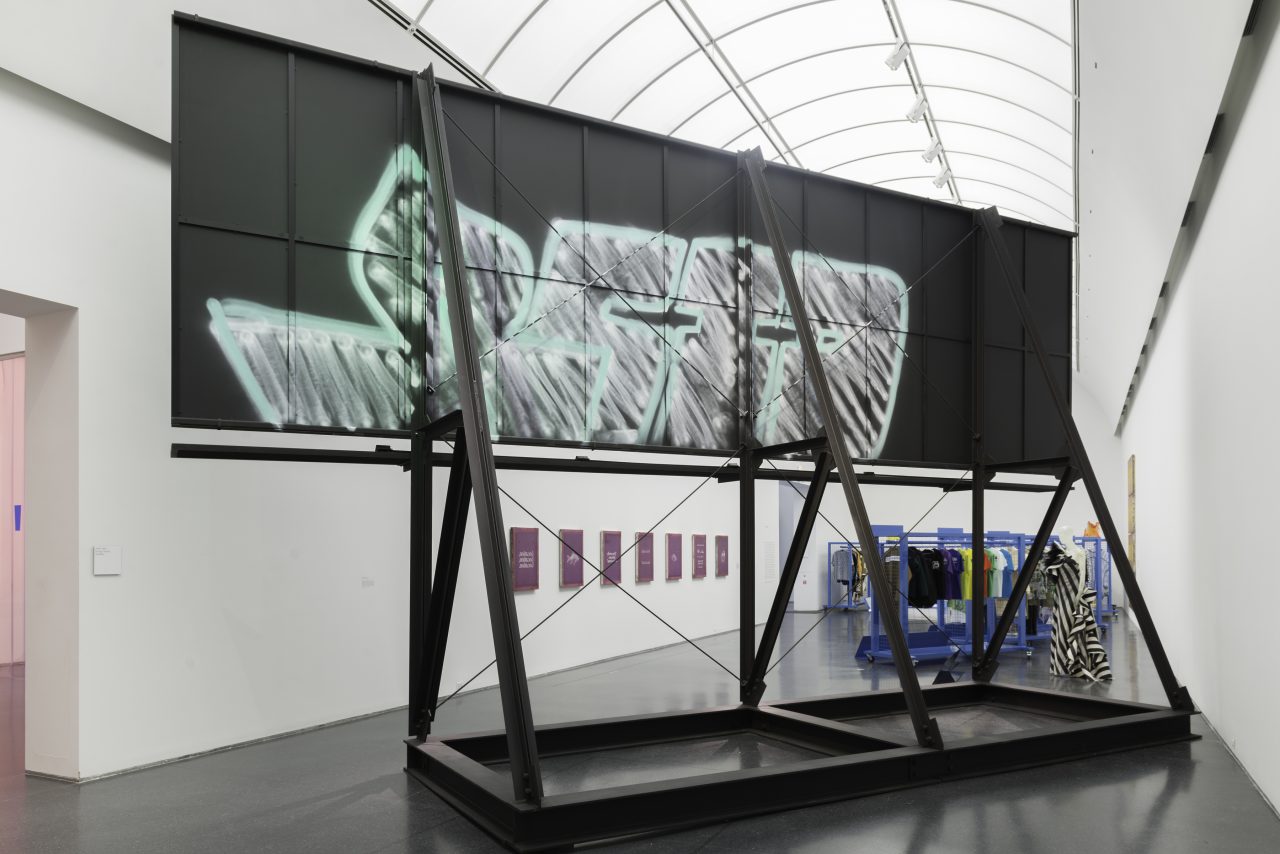

If you were an architecture student who happened to read Content more carefully than you did SMLXL, like Abloh clearly did during his time studying architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, you would have taken note of an introduction from its editor-in-chief, Rem Koolhaas, that read: “Maybe, architecture doesn’t have to be stupid after all. Liberated from the obligation to construct, it can become a way of thinking about anything – a discipline that represents relationships, proportions, connections, effects, the diagram of everything.”[i] The quotation serves as one of the many through lines of the exhibition proper (and foreshadows Koolhaas’ abrupt but pointed essay in the exhibition’s catalog, After Architecture) as it unfolds over seven stages and many more creative disciplines that constitute the 38-year-old’s career: Early Work, Fashion, Music, Intermezzo, Black Gaze, Design, and The End. As the chapters suggest, the subjects and mediums are vast; combining textile, video, sculpture, painting, graphic design, furniture, and even a building proposal for Chicago’s riverfront dating back to Abloh’s graduate thesis. Some of the work is known only to early followers; see the “Pyrex Vision” video. Some of the work is more well-known; see the “False Façade” collaboration with Fabien Montique. Some work is new; see the exquisite floor sculpture, “Options,” that arrays yellow number markers to warn of a crime scene. And some work is even credited to others; see “Screen Shot” by fellow artist Arthur Jafa that blows up a smartphone screen grab of Abloh Facetiming his friend the rapper Theophilus London. Although the work is often self-referential, allowing access primarily to those millions who follow Abloh on social media, the work is also paradoxical.

[i] Koolhaas, Rem, Brendan McGetrick, and Simon Brown. 2004. Content. Köln: Taschen.

And here is where the exhibition succeeds. While the stew of purist/tourist messages are as scattered as the mediums deployed, the quantity of works (relative to Abloh’s actual output) are few. The catalog purports of prototype, whereas the degrees of precision and taste on view suggest beauty and refinement (even the sketch Nike sneakers). The pace is also distinctly slow in comparison to how the artist and his audience normally interface (Instagram vs. real life). Most paradoxical, still, is how the tone of the exhibition, despite its democratic aims to level high and low cultures, mistakes cool for irony.

The art critic Dave Hickey once argued that “irony and cool are incompatible means to the same end.”[i] If irony is designed to suppress art’s meaning, then cool exists to suppress that meaning’s urgency. Imagine a party: irony antagonizes its guests, while cool simply mingles. Irony is often cited as Abloh’s foremost cultural contribution (i.e. “luxury” made popular), but the label is misguided. Actually, the work registers quite literal within the context of an art museum. The mask that once reveled in concealing angst, or antipathy, toward fashion norms looks to have been removed to reveal a sincere smile. Abloh’s penchant for coded language (see neon sign from a 2016 Off-White runway show, “YOU’RE OBVIOUSLY IN THE WRONG PLACE”) may position his work alongside that of Marcel Duchamp and other surrealist disruptors, but the physical artifacts and their labored investigations into process, materiality, and value systems appear to have more in common with cooler American artists, like early Andy Warhol or Alex Katz. Certainly, these masters, too, are included within the constellation of references that constitute Abloh’s dichotomous purist/tourist theory, but not nearly as much as the beloved ironists. So, here is one takeaway: if the work desires to question commodity capitalism, declare (not decry) racial stereotypes, expand social awareness, decouple building from architectural thinking, all amidst the borrowed details of a mid-century Modernist then it does just that. Let transparency guide meaning as it does in the room, Black Gaze, in which sculpture, photography, and painting weave together a tapestry of cultural signifiers designed to be consumed calmly, over time, and folded into a lifestyle, as well as an ideology. Like Arthur Jafa’s affecting film “Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death,” on display two stories below within the same museum, Abloh’s work is self-evident. It is serious without needing to project its seriousness under the guard of irony. If anything, let Warhol be your lawyer, Mr. Abloh. Or better yet, just be.

[i] Hickey, Dave. “American Cool.” Art Issues January-February (1999): 11.

Header image: Installation view, Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech”, MCA Chicago June 10 – September 22, 2019 (Nathan Keay, MCA Chicago)