Last April, an initiative to extend the legacy of famed midcentury design duo Charles and Ray Eames was launched by curator Llisa Demetrios, one of couple’s five grandchildren. The Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity, led by Demetrios, taps into Charles and Ray’s impressive collection of drawings, photographs, letters, sketches, models, and more to inspire creative problem solving for future generations. With the help of Airbnb cofounder Joe Gebbia, the Institute has continued to archive the collection, launched three digital exhibitions, started renovations to convert the family’s William Turnbull–designed ranch into a visitor center, and acquired San Francisco’s iconic William Stout Architectural Bookstore.

This week, AN Interior checks in with Llisa to learn more about these impressive efforts, what they mean for her family, and what her aspirations are for the future of the Institute as it enters its second year of operations.

Sophie Aliece Hollis: There are two other Eames organizations that predate The Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity: the Eames Office, which continues product manufacturing and production, and the Eames Foundation, which protects and preserves your grandparents’ former home in Los Angeles. How does the Eames Institute complement and add to the missions of these existing initiatives? What inspired the addition of this new arm?

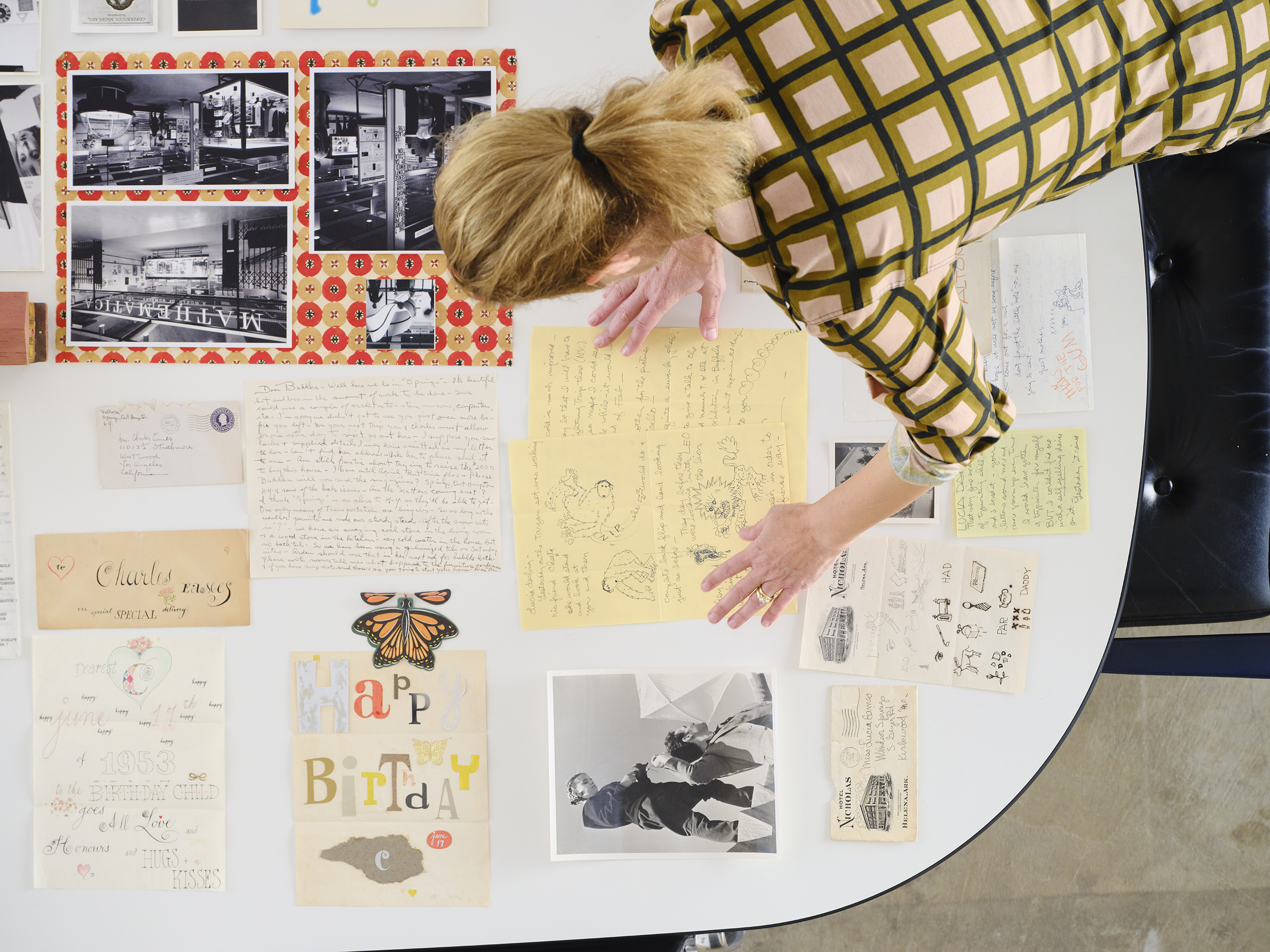

Llisa Demetrios: Upon looking through the collection of Charles and Ray’s things that my mother Lucia Eames inherited, my siblings and I quickly realized that this mass of material, some 50,000 documents and objects, could be used as an opportunity to learn how Ray and Charles solve problems: how they iterated and prototyped their ideas. So, we began iterating ourselves on how best to share this information. I’ve always believed that my grandparents’ work is participatory, so we wanted to develop the Institute to not only reflect on the legacy of my grandparents but also apply their ideas and their thinking to the future.

SAH: It sounds almost like a design charette, with constant iteration. When did the idea for the Institute begin to take shape?

LD: Our family had loaned about 400 objects to an exhibit that began at Barbican in London in 2015, a year after my mother passed away and left us the private collection. The exhibit ended in Oakland, California, in 2018 after becoming one of the most popular exhibits ever shown at the Oakland Museum. When it left, there was a void in the community—so much learning was still taking place when the exhibit closed, and people really missed it. Around this time, we were already in the process of archiving and inventorying nearby at our family ranch in Petaluma. That was when we really started to think about how and where to share this archive with a larger audience. Because of COVID-19, we pivoted to a digital launch, which ended up being able to reach a larger audience, but now we’re working on renovating the ranch to become a place for the community to visit and explore my grandparents’ ideas.

SAH: Your mother lived at the ranch, you’re currently living at the ranch, and now the ranch has become the headquarters of the Eames Institute of Curiosity. Could you speak to the history and significance of this place? And what are your aspirations for its future?

LD: William Turnbull designed the ranch for my mom in the early 1990s. His sister was a neighbor of ours in San Francisco and we had been up to Sea Ranch many times. My mother loved the flexibility of the spaces and wanted this place to house the collection she inherited from her parents. For context, when Ray passed away in 1988, ten years to the day after Charles, the directive was to donate much of their archive to The Library of Congress. But even after sending 750,000 slides and many files and folders, it looked as though nothing had been removed. What was left was my mother’s favorite part of their story: design with a lowercase d. When you go to an office or a restaurant and you see Eames furniture, that’s design with a capital D—but how did they get there? That’s what remained: thousands of drawings, sketches, notes, studies, photographs, prototypes. Charles always said, “Just because you know how a rainbow works, it doesn’t take away from the magic of it.” So, while my mother was still alive, we began archiving and inventorying this massive resource in order to share their designed objects and the stories around them.

Through word of mouth, designers, architects, and brands in the Bay Area heard about this collection and asked to visit it. Even Joe Gebbia had brought his team from Airbnb, along with other big tech companies like Pinterest, Instagram, and Facebook. When my mother passed away in 2014, we were considering selling the ranch and continuing the archiving elsewhere, but Joe stepped in and we figured out a way to continue the work that we were already doing, right here at the ranch. We acquired the building to become part of a nonprofit. In the process, we began to realize that this place is more about the 27 acres of agricultural land, so we started to share the collection digitally and are now focused on a renovation that positions the ranch as a hub for environmental stewardship.

SAH: What does that stewardship look like?

LD: We’re effectively applying my grandparents’ ideas to the outdoors. Most people are introduced to the Eames legacy through a chair, which is marvelous, but they don’t realize that, in designing the chair, Charles and Ray were considering society as a whole—the object, the space it inhabited, and how the sourcing of its materials affected the world around them. As early as the 1950s, they discontinued the use of Brazilian rosewood when they heard of its impacts on the rainforest. They did the same with plastic and fiberglass. So that’s what I mean by being better stewards of the environment: Being sensitive and aware that nothing happens in a void. We’re bringing that to the ranch in a few ways. We’ve begun installing solar panels with the goal of going completely off the grid. We’re very careful about our use of water, especially in this area where wildfires have damaged so much of Northern California. We’re sensitive about what we plant in the garden, ensuring that the fruit trees are supportive of the local plant species and any new ones we introduce. We have also started working with our neighbors across the way to restabilize a creek that runs through our properties. We’re trying to take this small swath of land and think about the interconnectedness of its many systems, just as Ray and Charles did in their designs.

SAH: I can imagine if they were still here today, tackling the world’s climate concerns would be at the forefront of Ray and Charles’ practice. In just under a year, you’ve continued to archive, launched digital exhibitions, and started this work at the ranch. The Institute also recently acquired beloved San Francisco institution, William Stout Architectural Books. What was the impetus for this acquisition and how does it tie into the overall mission of the Institute?

LD: It just seemed like a natural fit. Having grown up in the Bay Area, I am a huge fan of this bookstore; it’s a landmark. You could say that just as Ray and Charles have shaped a generation of designers; this bookstore also shaped a generation of architects. In the same vein as Joe’s ambition to figure out how to continue the legacy of Charles and Ray, we wanted to do so with William Stout’s. The intention was never to replace anything, but to figure out how to share it more. When Bill was thinking about retiring, we asked ourselves “How can we preserve this? How can we take care of this place that stewarded a whole generation?” It’s been as natural fit, parallel with the design intentions of my grandparents. And it’s been an honor to work with him.

SAH: You grew up immersed in this world of Eames. How do you think that personal history positions you to continue their legacy.

LD: Ray always told us growing up, “Whatever you do, only share what you understand.” I have lived on the property with the collection, I have a deep level of immersion with it. And I am constantly continuing to learn from it. When you’re steeped as deeply as I am, you begin to see the connections between the objects, the drawings, the ideas, the materials. But anyone coming here can make their own connections. And I think this is why it meant so much to my mom to keep everything together. There are so many opportunities for this found learning and my goal is to invite people to experience it for themselves.

I feel as if I am a conduit for people enter this world of Ray and Charles, I can show them a starting point. My grandparents always said that an exhibit can’t show everything on a subject, but you can show six to eight things that encourage people to do their own research.

SAH: The mission of the Institute is quite clear, in theory. What does that look like in practice down the road?

LD: When designing, Ray and Charles would always consider a chair in 25 years. They didn’t really care how it looked; they just wanted to know if it was still doing its job. You’re kind of asking me the same question. Eventually, I want the Institute to be a place where school buses come and learn from the material. In this first year, we’ve launched digital exhibitions and held pop ups in New York City. There have been so many things going on. But we’ve realized there are constraints—namely proximity and space—to doing it here on the property. The next big plan is to find a larger location where we can properly show the material, host workshops, play films, and encourage conversations around the work. I imagine this will look like a larger venue in the Bay Area where we could house and take care of the collection as well as finish the archiving and inventory.

For now, I am here in my little corner, picking away at the archival material. I really believe sharing this resource is going to help change the world. I would love to be able to show Ray and Charles what we’ve learned from this. I go to sleep thinking about how they would do things, how they would make it more available to everybody. But to reiterate, this is really an opportunity to take the ideas that they shared and use them in our own ways. We’re not trying to be Ray and Charles; we’re trying to take what we can learn from them and apply it today. The landscape is constantly changing, and the constraints are evolving. I wish they could be here to see how we’re addressing them. I’m very excited about it. To me, this is just the beginning.

SAH: Well, it has been an incredible and impactful beginning. It won’t even be a year until next month.

LD: You’ll have to follow up in another year to see how far we’ve gotten!