Located a few miles from the Alamo on San Antonio’s south side, Riverside Baptist Church consists of a modest complex of brick structures built over the course of several decades. The sanctuary’s engaged portico expresses vaguely classical details and is flanked by an educational building and a fellowship hall that more explicitly reflect the eras of their construction. But the photographs collected in The Things Not Seen Are Eternal do not dwell on the exterior of these buildings. Instead, they explore the seen and unseen artifacts found in their vast, depopulated interiors.

The photographer, Herman Ellis Dyal, spent much of his childhood inside Riverside Baptist Church. As explained in a concise essay appending the collection of documentary photos published by GOST Books in April, the 1950s of his youth was “the high-water mark of institutional Christianity in Eisenhower’s America, and we were in one of the city’s largest and fastest-growing churches.”

But just as Dyal’s own beliefs have changed since then, so too has the prominence of community churches like the one he attended. As its congregation dwindled in the second half of the 20th century, the faithful retreated into ever-smaller portions of the large complex of buildings it once saw fit to build. Even so, the disused portions of the church retained evidence of their past use, and these semiabandoned spaces became the focus of Dyal’s photographic study.

Although he trained and worked as an architect (with early stints at both SOM and in Philip Johnson’s office), Dyal spent most of his career exploring the intersection of graphic design and the built environment. His firms—fd2s, Dyal and Partners, and Page/Dyal Branding and Graphics—brought together the disciplines of architectural design, industrial design, and experiential design. This interdisciplinary approach is reflected in the images collected in this monograph, as they possess an indelible quality that is at once both graphic and spatial, objective and impressionistic. The liminal spaces they depict sit similarly between worlds: They contain artifacts of human occupation while being completely devoid of people.

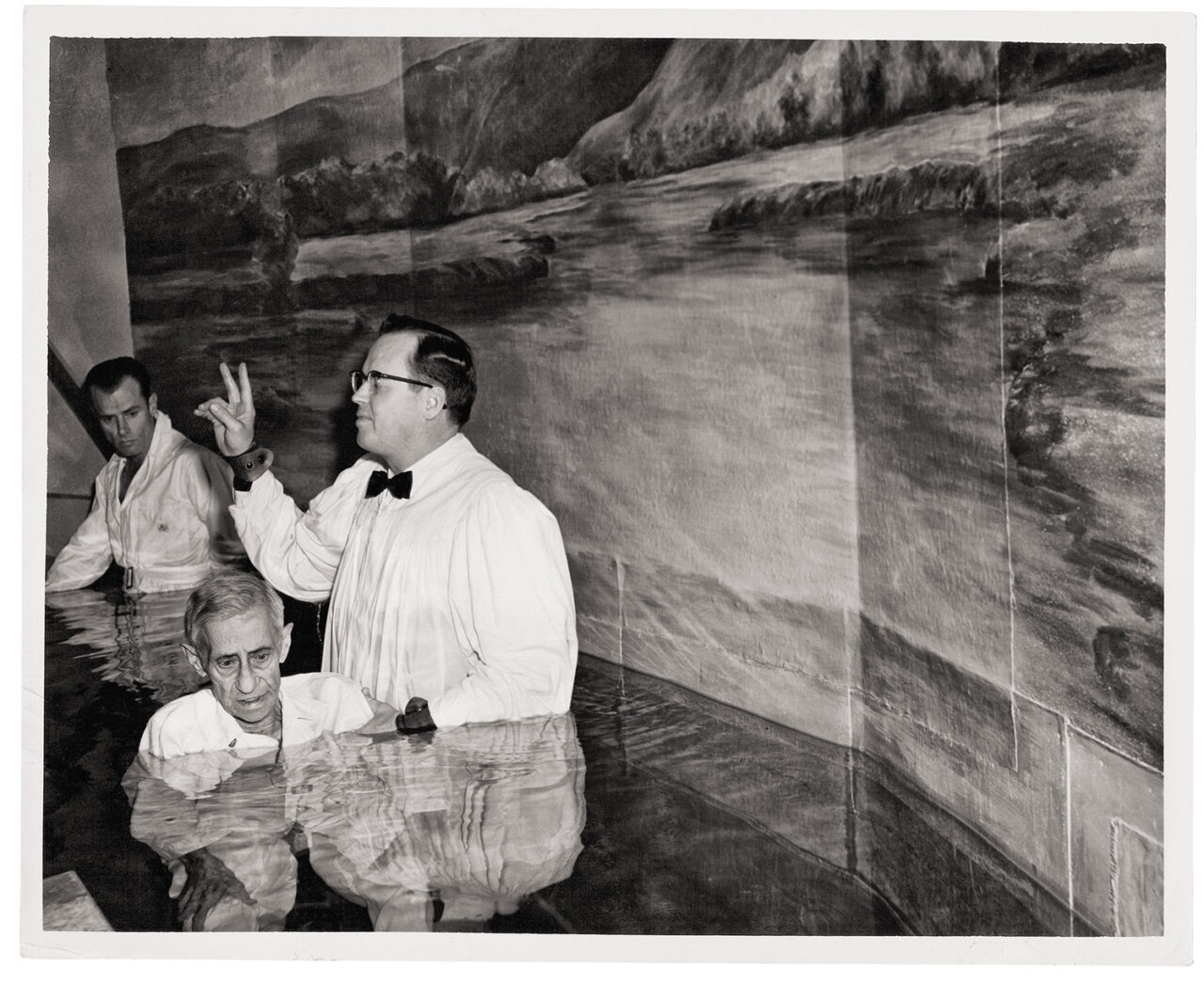

Even though the project was deeply personal for Dyal—he admits this in the concluding essay—the evocative images speak to the universal experience of loss. Presented without captions or other descriptive text, the photographs generate questions that engage more than frustrate. Was the bouquet of plastic flowers left behind after a funeral service? Is that a baptismal pool drained of its holy water? Is this what the world will look like after the rapture and/or the next pandemic?

The book’s final photographs were not captured by Dyal but are instead reproduced vintage photographs of Riverside Baptist Church in its heyday. These images answer some of the questions asked by Dyal’s photographs—yes, that was a baptismal pool—but they leave the viewer to continue to ponder larger issues of meaning, memory, and mortality.

Is a church a building, or the people who worship there? What is to be done with relics of the past when no one is left to remember that past? What, besides bouquets of plastic flowers, is truly eternal?