Mexico City’s art scene was on full display during this year’s semana del arte, a weeklong culture-and-commerce festival that has grown into a glitzy international attraction, packed with appointments and open mezcal bars that vie with the art on offer. Between Zona Maco, the big, blue-chip fair, and several independent salons, smaller happenings lure visitors to traverse the metropolis for viewings in unexpected settings. Even in a city with no shortage of recondite locations, many compelling sites tend to be off limits, requiring patient scouting and brokering by gallerists and curators. But no one is better at securing normally impenetrable, pedigreed architectural gems for its research-based group shows than PEANA. (The gallery’s permanent home, designed by local firm oioioi, is in a former gym in the Roma Sur district.)

After exhibitions at Ernesto Gómez Gallardo’s Möbius house (2019) and Agustin Hernandez’s skybound sci-fi lair (2022), this year PEANA founder Ana Pérez Escoto convinced the family of Conlon Nancarrow to allow part of the house Juan O’Gorman co-designed for the experimental composer around 1949 to host a thought-provoking and playful tête-à-tête between the works of 24 artists, titled A Stubborn Man and a Hermit Walk Into a Bar. Some were created specifically to respond to the venue—a one-of-a-kind space that was the product of a special friendship between composer and architect. O’Gorman is best known for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo’s twin houses and for his mosaic-covered library tower on the National University’s campus (UNAM). But between those two projects, the politically engaged O’Gorman, who was also an accomplished painter, underwent a radical change of heart.

O’Gorman and his peers were concerned with how an imported new style of building could best be adapted to Mexico’s character and traditions. During this reckoning, the Nancarrow House, situated in the Las Aguilas neighborhood, occupied a mythical place. It is here that O’Gorman, influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright (he had visited Fallingwater in 1938) pivoted away from Corbusian functionalism to a figurative, texturally rich, and organic language, deploying local materials like volcanic stone to striking effect. The house’s distinctive feature is a series of “petro-murals,” expansive polychromatic mosaics assembled from hundreds of little stones. These elaborate stone “drawings” which O’Gorman used here for the first time on exterior surfaces depict a pantheon of eagles, jaguars, and Aztec deities, as well as spiritual symbols from Yin and Yang to astrological signs. As a bonus, O’Gorman’s murals are currently complemented by a series of more recent works jointly selected by Pérez Escoto, Mercedes Gómez, and Joseph del Pesco.

The co-curators narrative centered on the home’s lived-in objects. . . and secrets. There was a fertile trove of stories to work with: Nancarrow was a fascinatingly inventive, and at times contradictory, character who had to flee the United States in 1940 due to his Communist affiliations. The composer and O’Gorman’s shared frustration with humanity elicited a kindred posture—a kind of solitary, post-idealist opposition through sui generis art (hence the show’s winking title).

The first section of the exhibition is a suite of connected rooms: the now enclosed porch; Nancarrow’s colorfully tiled kitchen; and a handsome wood-paneled room. The works on display here give a sense of the diverse range of artists included in PEANA’s show: from the late self-taught Goulven Elies, whose bronze and wood womb sculptures look oddly at home in Nancarrow’s cooking area, to a noisy multi-medium piece by the Milpa Alta-based artist and environmental activist Fernando Palma, age 67, to emerging stars like Aureliano Alvardo Faessler, age 26, whose encased painting—intimate, totem-like, and hyper-contemporary in equal measure—was one of the first items to be snapped up by a collector. More artworks can be found in the property’s extended patio and garden areas, among them Tomás Díaz Cedeño’s intervention in what once was a small pool. Today it’s temporarily recreated as a shallow hydro-mural, a glistening sheet of water atop bas-relief terracotta panels the artist produces in Michoacan.

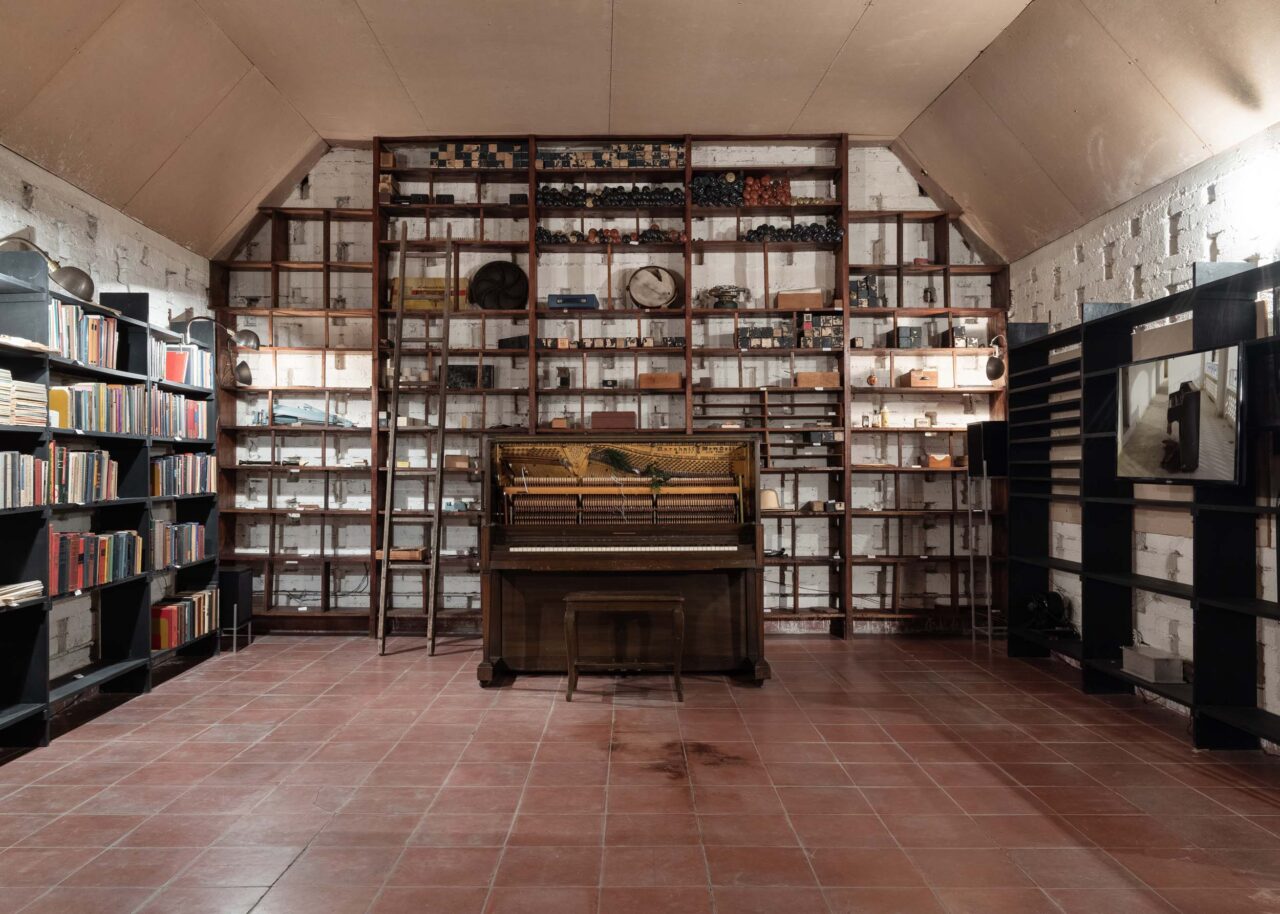

Nancarrow’s sprawling two-story library, replete with tomes on sex, psychology, and language, is the next section of the house interspersed with new works. Lima-born Ximena Garrido-Lecca uses a Javascript program in here to weave copper wire into patterns typical in Indigenous textiles, while two mechanized works by Lucas Cantú take to a literal, somewhat prank-like manifestation the rumor that Nancarrow’s ghost lives on, perhaps hidden in the library’s cramped winding staircase. Nearby, the composer’s studio is a universe unto itself; an acoustic sanctum where he recorded the more than 40 Studies for Player Piano that, in Nancarrow’s 1997 obituary, the New York Times described as “dazzl[ing] the ear with torrential figuration, thick counterpoint, colliding meters and melodies that draw on everything from blues… to the spiky abstractions of free atonality.” Here, two video works by Lenka Clayton and Phillip Andrew Lewis and Carolina Fusilier and Miko Revereza riff on the composer’s oeuvre. Another musical exhibition, especially composed by Darío Acuña Fuentes-Berain, moved at least one visitor to tears.

The adjacent workshop where Nancarrow liked to take apart and tinker with musical instruments hosts Carlos Matos’s work. It perfectly conjures the “Stubborn Man” leitmotif of art’s potential as a form of resistance. Inspired by a Leonard Cohen quip about the grace found in surrender, Matos designed a human-shaped rocking chair from flat wood boards, a type of wise-man’s perch, at once restive and resting. If O’Gorman—a famously ardent leftist who grew increasingly disillusioned with the way his socially minded works were co-opted by corrupt systems—might have objected to the rooms he conceived being used to sell art that is out of reach for the majority of his country’s population, one can imagine him finding reluctant solace in Matos’s chair.

O’Gorman’s reclusion in art worked as a coping mechanism only for so long: He took his own life in 1982. Similarly, his home’s survival isn’t guaranteed. Touching a slightly somber yet poignant note, Adriana Sandoval, director of the Espacio Nancarrow Foundation, was on hand to remind the art crowd of the premises’ precarity. Like any private property not officially declared a monument, Casa Estudio Nancarrow faces an uncertain future.

A Stubborn Man and a Hermit Walk into a Bar is on view until March 3.