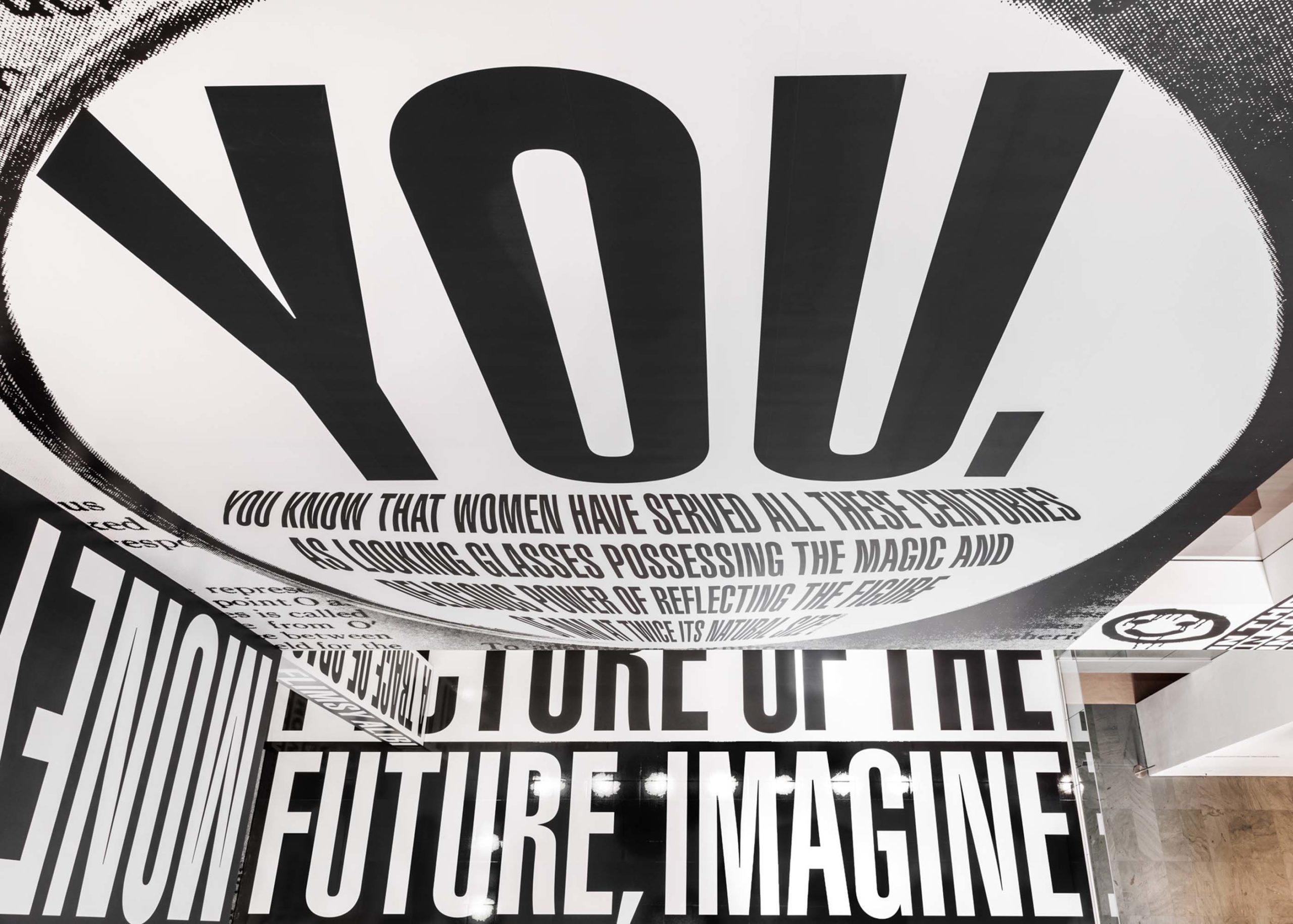

In October 1928, Virginia Woolf delivered a pair of lectures collected a year later as A Room of One’s Own. “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size,” she wrote.

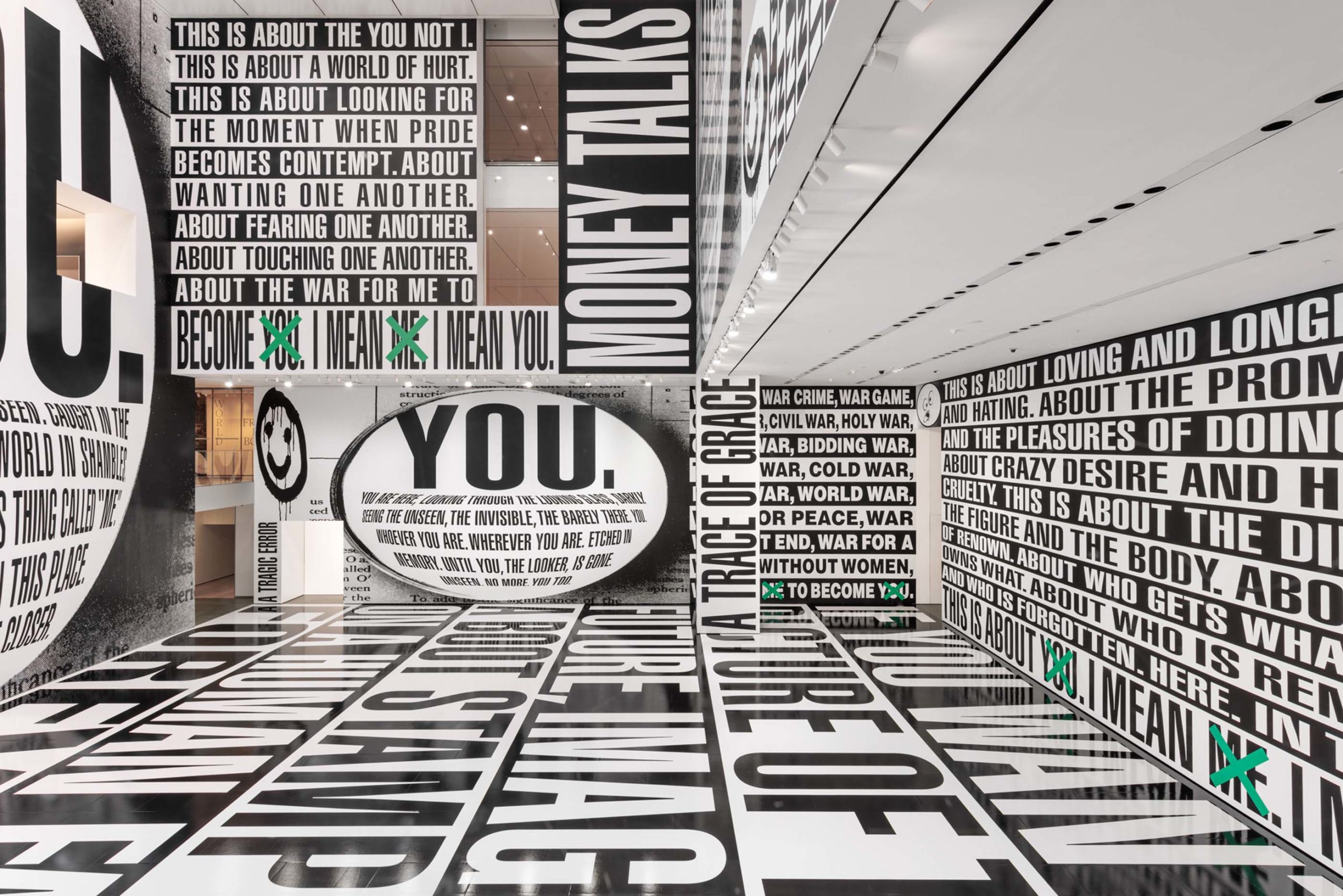

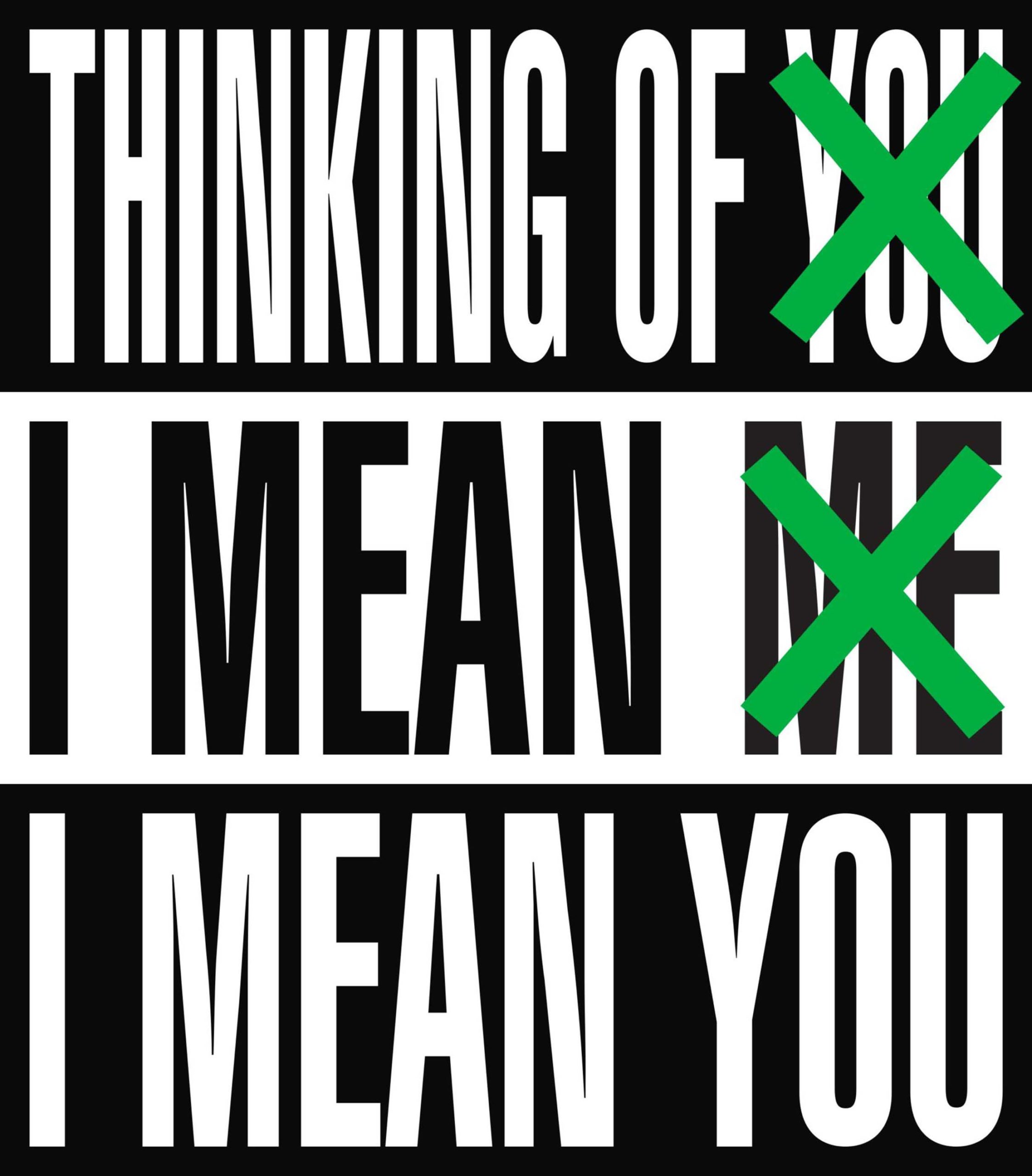

This fall, Barbara Kruger, among the true art superstars of her generation, has covered one wall of MoMA’s Marron Atrium with an expansion and renovation of Woolf’s famed quote. Her show, Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, is a truncated rethink of the expansive solo exhibition that ran at LACMA this spring and at the Art Institute of Chicago before that. Perhaps MoMA’s curious decision to give her the atrium and no more was a matter of scheduling—but, never fear, it’s their loss. Yet another show of her work filled three entire New York City locations of the mega-gallery David Zwirner this summer. (A big version of her 1989 piece Untitled [Your Body is a Battleground] was on view in Chelsea, right on time for this summer’s overturning of Roe v. Wade.)

Kruger’s magic and delicious power has been easily accessible since the late 1970s. It’s in her words—quick statements that don’t take their factual status as a given—or simple questions that beget queasy complications. I Shop Therefore I Am. Who is free to choose? On and on. It’s also in the graphics of her delivery: words on placards (or maybe cages) of solid red, or black, or white, below irresistible language printed in authoritative Helvetica or Futura Bold. Backgrounds occasionally appropriate vintage illustrations for a ballast of history or to bleed out the past. And it’s in her design: Since the ’80s, the Kruger brand stands for a blend of the seductive textual teasing of Burma-Shave billboards, the elusive eureka of a pamphlet’s Zen koan, the dizzying pleasure of Barbara Stauffacher Solomon’s late ’60s supergraphics, and the dexterous word games of queer and feminist theory.

Her minimalism hides the seams—you know it when you see it. In the preeminent sign of Pop Art success, it’s been widely bootlegged. In 2013, the blockbuster style vultures Supreme had the temerity to sue streetwear brand Married to the Mob for copying their white-on-red lettering, which anyone could see was a big Kruger bite. She called the situation “a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers,” bankrupting the whole scene in seven words.

So how does the new work hold up in MoMA’s giant atrium? Its west wall sets Woolf’s words within a flattened funhouse mirror, itself set against a spattering of newsprint-ish halftone dots; the effect surprisingly and audaciously cuts the room to size. Below it, she installed lines of black and white text—THIS IS […] ABOUT WHO IS REMEMBERED AND WHO IS FORGOTTEN. HERE. IN THIS PLACE—and then the show title, with the words YOU and ME x’d out in a green not far from the all-clear lights of MoMA’s nearby metal detectors. Structural columns are clad in phrases like A SMUG EMBRACE. Another circle consumes the east wall, this one reminiscent of a magnifying glass with a huge YOU, followed by YOU ARE SEEING AND BEING SEEN.

On my visit, the entire enterprise was a popular backdrop for selfies. As was the floor, covered in vinyl printed with words by George Orwell: YOU WANT A PICTURE OF THE FUTURE, IMAGINE A BOOT STAMPING ON A HUMAN FACE, FOREVER. If you kneeled and smiled up to a friend photographing precariously from one of the glass balconies, it made for a hell of a pose.

Just around the bend from MoMA’s permanent Lawrence Weiner mural—a prime example of his own instantly recognizable branding that reads A BIT OF MATTER / AND A LITTLE BIT MORE—Kruger’s unwavering dedication to her strategy reads like insistence that she’s right. Of course, she mostly is, although sometimes the lists stumble into ambiguity when one hopes for certainty. There’s a whiff of trans-exclusionary radical feminism (TERF) innuendo in the phrase WAR FOR A WORLD WITHOUT WOMEN, for example, that one prays is inadvertent. Or does Kruger mean that TERF war? Two tiresome smiley-face icons on either side of the wall held no answers. But otherwise, absolutely, dead right. IN THE END, HOPE IS LOST reads a line that climbs a wall and ends in blank white pain. I hope she’s wrong about that.

Kruger’s efforts only just predate the rise of the 24-hour news cycle, which is constantly littered with chyrons that could easily have been fashioned by a Kruger bot. MoMA’s installation shouts its slogans blocks from the endless scroll of the Fox News zipper at Rockefeller Center, a geographic reminder of how money has buoyed the contemporary art market.

Some 86 years after Woolf’s initial talks, MoMA opened Yoshio Taniguchi’s expansion and renovation of its Midtown headquarters in 2004. Financier/philanthropist Donald Marron—a benefactor, as CEO of PaineWebber and then chairman of UBS America and then founder of Lightyear Capital, of the excesses of late capitalism, and, as curator of PaineWebber’s immense, touring corporate art collections, a 20th century pioneer of fine-art-as-asset—and his wife Catherine raised a vast chunk of the reported billion dollars it took to build the museum’s vertical campus, which includes the atrium that rises 110 feet in height.

Running vertically and stretched out, a key phrase hovers like the sword of Damocles above the room: MONEY TALKS. True, and yet the wall that gave me most pause was the one across the way. Entirely white, dappled with streaks of natural light from the skylights above, the wall displays a few tiny words that are exponentially louder in meaning. They read: The Donald and Catherine Marron Family Atrium. Unlike the exhibition’s paint and vinyl, they’re here to stay. Like Woolf, Kruger might try to cut men in power, like Marron, down to size. But this room is still his own.

Jesse Dorris is a writer in New York City and hosts Polyglot, a radio show on WFMU.