What do the Rick Roll and Boris Yeltsin have in common? The cultural phenomenon and political figure were both fixtures of the late 20th and early 21st-century cultural zeitgeist; a time heavily defined by Generation X. Separate from the populous Baby Boomers and their Millennial offspring, this segment of western society was born between the late 1960s and early 80s. X-ers lived in a pre and postdigital world and were witness to how technology could transform culture. Coming of age at the turn of the century, this generation experienced the growth of globalization and a collective loss of innocence.

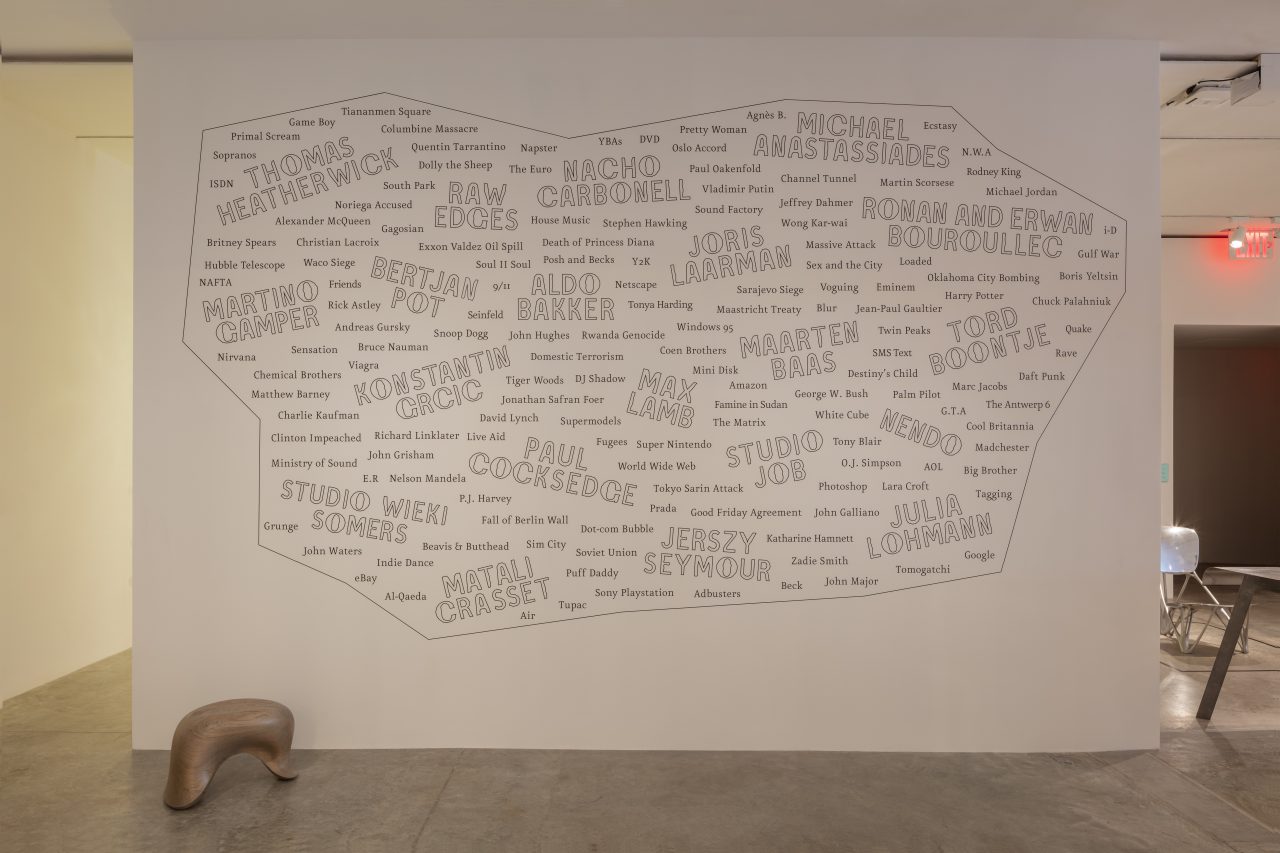

Currently on view at New York’s Friedman Benda gallery, An Accelerated Culture—closing on 8 June—is a unique group exhibition that seeks to survey rather than typecast design from this periodization. Mounted by London powerhouse curated Libby Sellers and Brent Dzekciorius of cutting-edge architectural material brand Dzek—a former art advisor in his own respect—the showcase incorporates an eclectic array of limited edition furniture, lighting, and accessory designs created by some of the United States, Europe, and Japan’s most recognized mid-career designers. A few of the works on view come directly from the gallery’s own roster of talents, such as Dutch talent Joris Laarman and British designer Paul Cocksedge.

“We started with the brief of looking at a generation of designers born between the mid-60s and early 80s. However, digging deeper we actually found a group of fiercely autonomous talents and couldn’t pinpoint an overriding ideology that connected them.” Sellers explains. “So the challenge for to us was to frame these talents within the context of the gallery. By doing so, we started seeing similar motivations; a level of exchange, energy, and a sense of community that allowed us to mark the moment from our present-day vantage point.”

For this project, Dzekciorius and Sellers drew reference from Douglas Coupland’s seminal 1991 book Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. In this novel, the author sought to identify the collective zeitgeist of the post Baby Boomer generation and ultimately characterized this group as apathetic; espousing a slacker stereotype. However, in the three decades, since the book was published, X-ers have proven themselves as a rigorous group of entrepreneurs. Undaunted by the mounting wicked problems facing the world—the ebbs and flows of production surplus, unstable periods of economic prosperity and uncertainty—these creatives decided to trek their own multidimensional paths. Many of the exhibiting designers have been able to successfully straddle the collectible, contract, and consumer markets; an ability that only a few contemporary emerging practitioners have been able to mirror.

“This was the first generation able to work with rapid prototyping, 3D computer drafting programs, and yet they did not grow up as digital natives,” Sellers adds. “They were caught in the middle of this awkward analog-digital transition and had to figure out how to respond to this rapid shift. They also demonstrated a sort of inherent or nascent awareness of sustainability and the ability to express commentary through design. This generation of designers was perhaps the last that actually felt that they could create work without an overwhelming sense of guilt, now associated with the ecological crisis.”

Regardless of this focus, Dzekciorius and Sellers didn’t curate the exhibit based on any historical lineage or hierarchy. Works produced 10 to 20 years ago are mixed in with a few newly commissioned pieces. The curators were careful not to select designs that signify a talent’s breakout moment but rather works that represent their established practices; a few years in.

London-based studio Dunne & Raby and Michael Anastassiades’s 2004-2005 Huggable Atomic piece sits next to Dutch designer Maarten Baas’ notorious, once controversial 2004 Where There’s Smoke Zig Zag chair: a charred wood iteration of a preexisting classic design by the famous 20th-century Dutch architect Gerrit Rietveld. Dutch talent Tord Boontje’s deeply personal and whimsical Perforated metal table, produced in 2001, flanks his Droog-esque Rough and Ready chair from 2004. French duo the Bouroullec’s colossal 2008 Triple Black Light barely makes it off the ground but manages to hang above this table setting. Nearby are Japanese design studio nendo’s 2015 Manga Chairs and Spanish Eindhoven-based Nacho Carbonell’s paper mache Evolution One Man Chair from 2008, accompanied by recent polypropylene rope masks by Dutch designer Bertjan Pot. Other exhibited talents include France’s Matali Crasset, the Netherland’s Aldo Bakker and Wieki Somers; Italy’s Martino Gamper; the UK’s Thomas Heatherwick, Max Lamb, and Raw Edges; and Germany’s Konstantin Grcic and Julia Lohmann.

Indicative of the period surveyed, An Accelerated Culture places a particular emphasis on Dutch design. From the early 1990s till the mid-2000s, this country’s output was perhaps the most radical and innovative. Similar to Italy in the 1970s and 80s, The Netherland—shaped by progressive schools like the Design Academy Eindhoven—produced or educated some of the design world’s most cutting-edge talents. British designers from top institutions like the Royal College of Art or Central Saint Martins also figure prominently in this exhibition.

“There were different reactions to Radical Italian Design from the 1970s, which became more commercialized in the 1980s. this explains Generation X’s pluralistic reaction,” Dzekciorius reflects. “Movements became less defined in the 1990s. There were those like Jasper Morrison who reacted to the Postmodern period with a renewed sense of minimalism. Dutch design platform Droog was more expressive. However, both were somehow part of an intermediate period of re-rationalization. In the latter half of the decade, it got boisterous again; a sort of Post-Postmodern period. And yet someone like Aldo Bakker, the son of Droog co-founder Gijs Bakker, maintained a restrained approach during this period. Unlike contemporaries like Maarten Baas or Tord Boontje, Bakker’s design never relied on irony or satire.”

No other curatorial endeavor, of this nature, has of yet attempted to codify a period so recent. And yet, it seems that some of the pieces on view have come from the deep annals of design history. like the exhibit’s name suggests, this proves that creative output and culture itself has sped up exponentially in the past few decades. Like at the dawn of machine age in the late 19th-century, the concept of the near-past has essentially been skewed by new technologies and modes of consuming information. Attention spans have yet again shortened. Andy Warhol’s adage that everyone gets 15 minutes of fame is coming to fruition in innumerable ways. The window of time in which one is able to achieve and enjoy recognition is fleeting. This exhibition seeks to slow things down a bit and offer a level of objectivity.