In 1920, western society was either embracing social progress and financial prosperity or bracing for political revolution and economic insecurity.

In architecture and design, a polarity would also emerge between the rationalist International Style and the eclectic Art Deco style. While certain practitioners and theorists were still trying to codify the form-follows-function principle—a tenet inspired by the rapid advancement of industrialization in previous decades—others were looking to reintroduce ornamentation and historical reference to soften the blow of this systemic change. An ongoing clash between purist and pastiche styles would come to define much of the following century.

Although architectural historians usually focus on monumental buildings and grand urban master plans to define styles like postmodernism and deconstructivism, those movements are also formed by domestic interiors. Our homes have always been an expression of the way we live. They mold our everyday routines and fundamentally affect our well-being. These environments reflect the social behaviors, cultural norms, and political beliefs that shape our time.

A new comprehensive exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum in Southern Germany validates the historical value of interior design and surveys its radical evolution over the past hundred years.

On view until August 23, Home Stories 100 Years, 20 Visionary Interiors brings together a group of emblematic projects. Spanning from the 1920s to the present day, this timeline of domestic design reveals how interiors have mirrored and, in certain cases, cemented societal shifts and technological innovations.

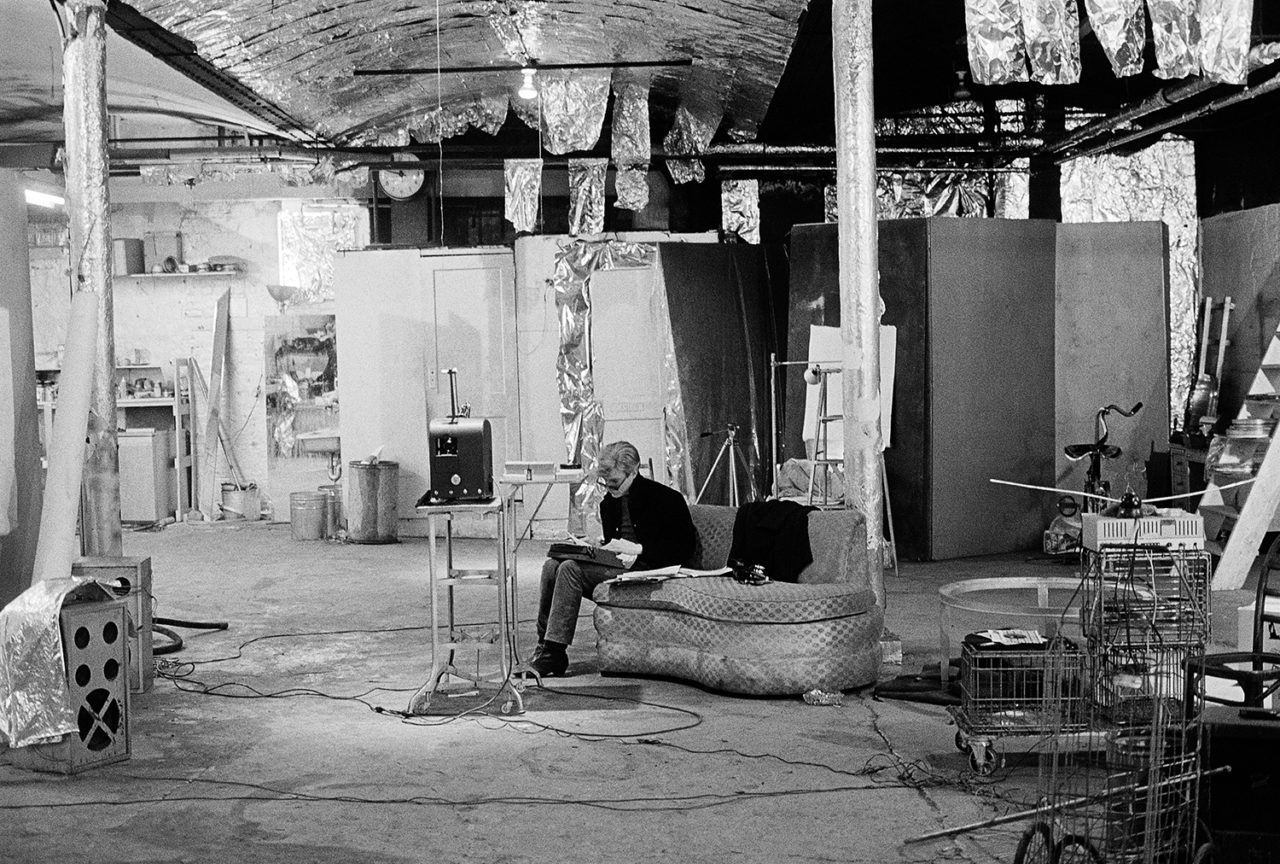

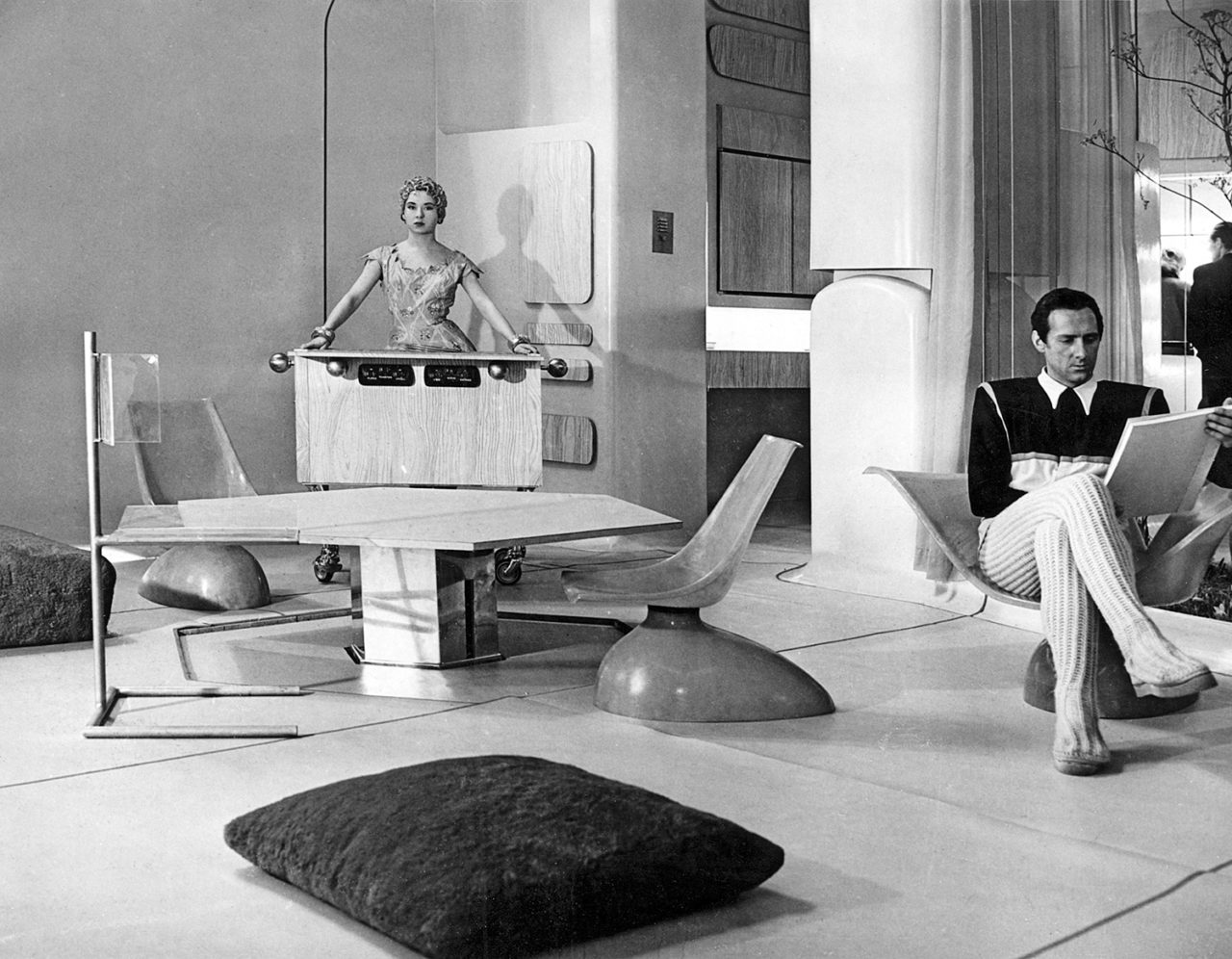

By looking back at such epochal moments as the introduction of appliances in suburban homes during the ’50s, radical interventions in the ’60s, and the loft living trend in the ’70s, the show provides context for the serious issues facing society today: the shrinking of urban living spaces, for example.

By presenting historic case studies conceived by Adolf Loos, Finn Juhl, Lina Bo Bardi, Andy Warhol, Cecil Beaton, Elsie de Wolfe, and Assemble, among others, the Home Stories exhibition explores how domestic interior design has spawned its own cultural following and economy—a thriving industry and a vast network of dedicated media outlets—but also how this domain has been underserved when it comes to public and academic discourse.

With the show and an accompanying lecture series, curator Jochen Eisenbrand and assistant curator Anna-Mea Hoffmann hope to establish that interiors are as intertwined with the pressing issues of the day as building exteriors and urban master plans.

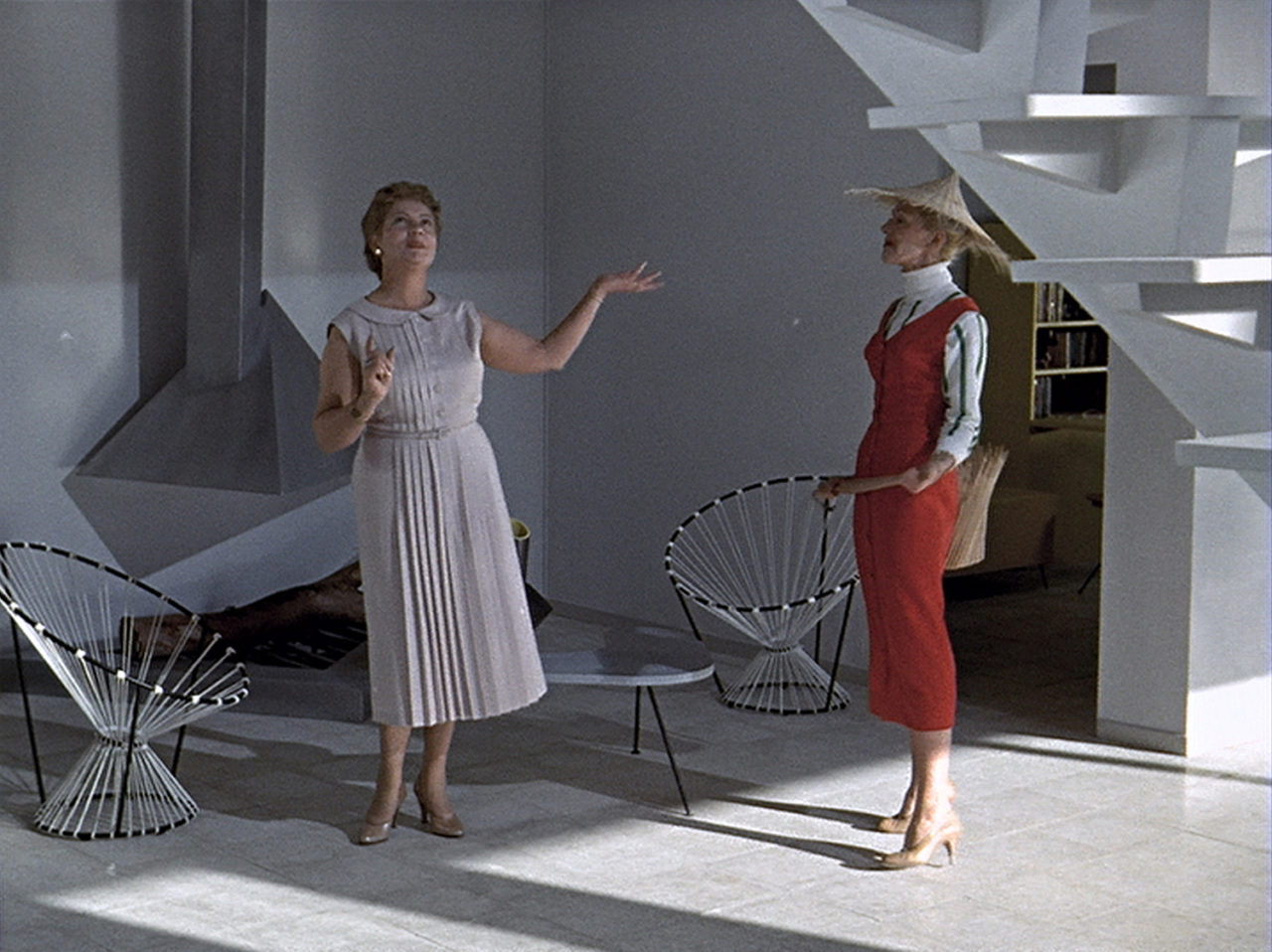

Broken up into four thematic sections: Space, Economy, and Atmosphere: 2000–Today; Rethinking the Interior: 1960–1980; Nature and Technology: 1950–1960; and The Birth of the Modern Interior: 1920–1940, the Home Stories exhibition incorporates historic documentation, photographs, drawings, iconic furnishings, and architectural models.

Images of Karl Lagerfeld’s Memphis Group–heavy Monte Carlo penthouse are displayed in jarring contrast to photos of Kishō Kurokawa’s Metabolist Nakagin Capsule Tower (conceived a decade apart). An image of Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev debating near a prototype of the prefab X-61 (Splitnik) house at the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow plays off of Finn Juhl’s 1959 Chieftain Chair, a symbol of restrained mid-century modern Scandinavian design.

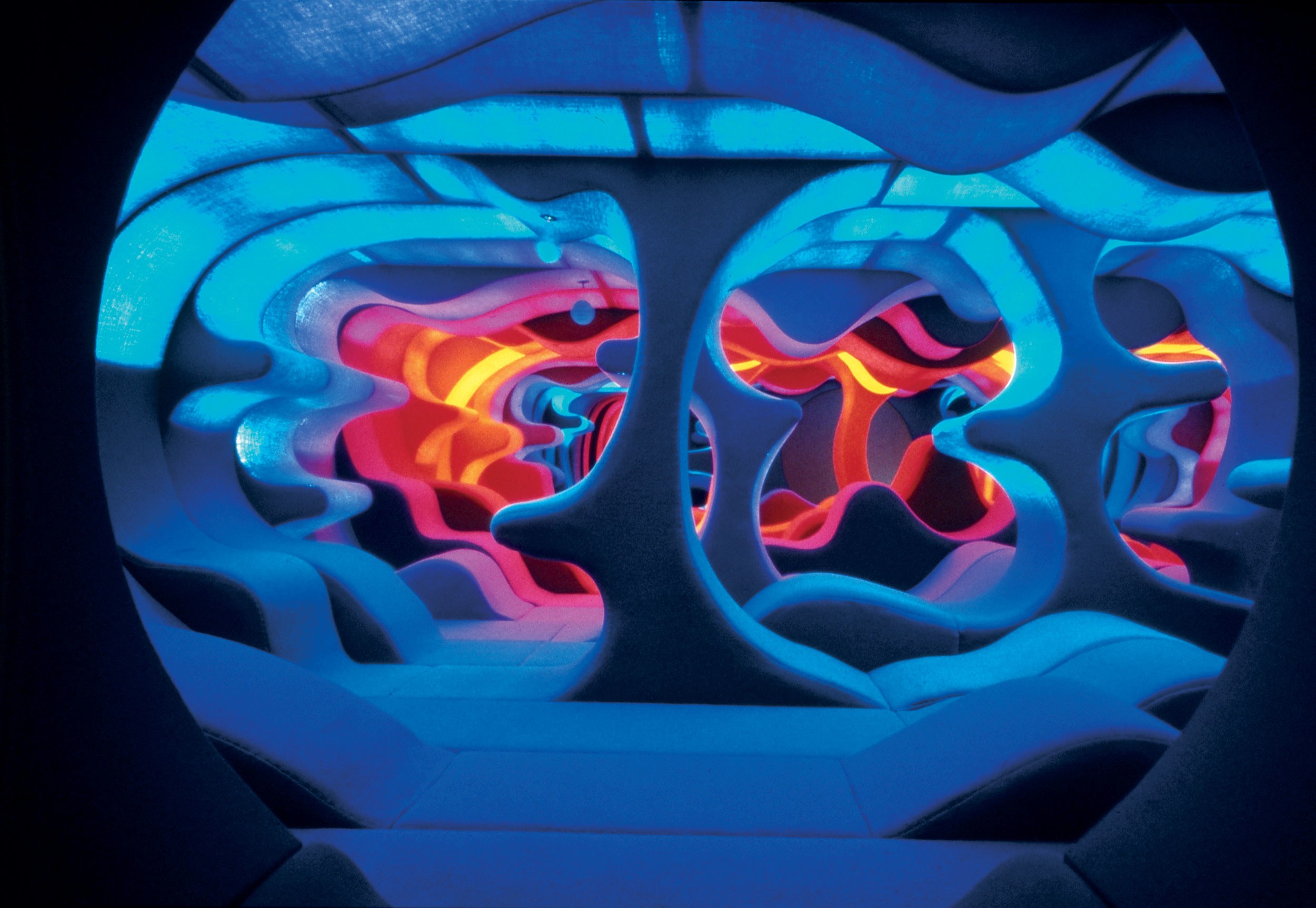

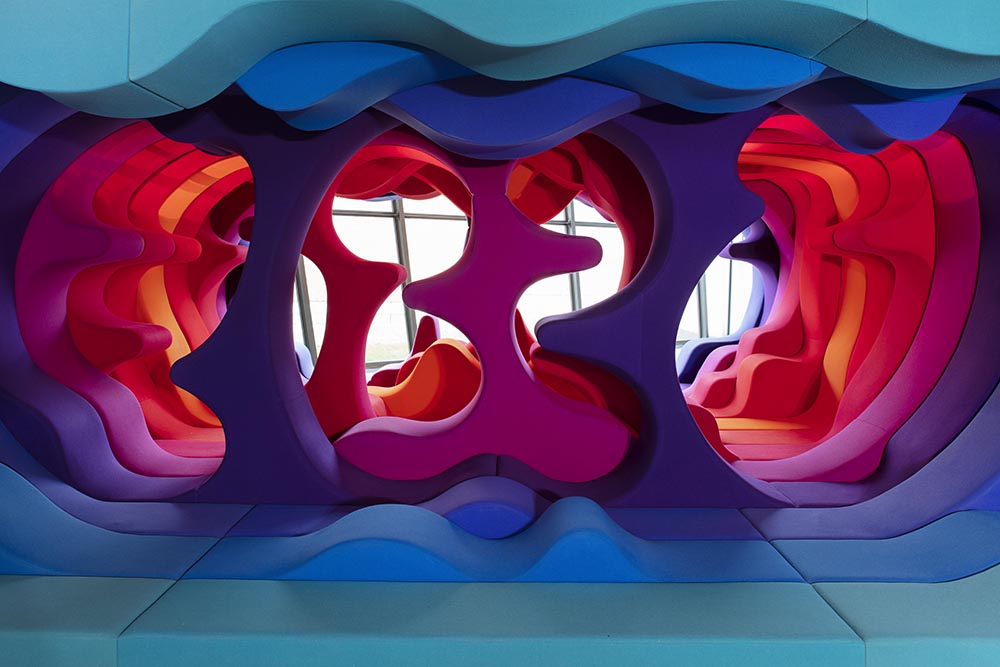

A reconstruction of Verner Panton’s space-age Phantasy Landscape installation—first shown at the Visiona 2 exhibition, as part of the Cologne Furniture Fair in 1970—is a clear contender for the title of best in show.

What comes across in the Home Stories exhibition is an aesthetic complexity and geographic stratification that disputes the traditional historiographic definitions of specific styles.

The exhibition is joined by an encyclopedic publication that includes contributions from curator and educator Joseph Grima, journalist Alice Rawsthorn, designer Ilse Crawford, theorist Penny Sparke, architectural historian Adam Štěch, and emerging interior designers Adam Charlap Hyman and Andre Herrero.

Header image: Verner Panton, Phantasy Landscape at the Visiona 2 exhibition, Cologne, Germany, 1970 (Courtesy Verner Panton Design AG, Basel)