Some time in 2014, architects Max Worrell and Jejon Yeung got a call from friends who had been looking for a beach house in the Hamptons to buy. The couple, a financier and an artist, had stumbled across a compelling find: a spacious modernist home in Amagansett, New York, about a block from the ocean. Only, they hadn’t heard of the architect named on the listing and rang up Worrell and Yeung to ask for their opinion.

“They called us from the house and asked, ‘What do you think of Charles Gwathmey?’” recalled Worrell. “We chuckled and told them, ‘It depends which Charles Gwathmey you mean?’”

He and Yeung, partners in a Brooklyn-based architecture firm that bears their names, first met as graduate students at the Yale School of Architecture. There, they were steeped in the modernist tradition to which Gwathmey (class of ’62) was heir, partisan, and, eventually, wrecker. A few years out of school, Gwathmey made a splash with a house he designed for his parents, also in Amagansett. It inspired endless copies and permutations up and down the East Coast, done by architects who never seemed to tire of the formal games one can play with platonic solids. Least of all Gwathmey himself. He would return to that well time and again until he, like many of his generation, thinking themselves great wits and savvy businessmen, switched allegiance to postmodernism in the 1980s. The quality of Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects’ (and later Gwathmey Siegel Kaufman & Associates Architects’) output nosedived, never to recover.

It’s a familiar story. But Worrell and Yeung became intrigued on being told that the house in question dated from 1976—not quite peak Gwathmey, but well within the “safe” zone of his portfolio. The Haupt Residence, as it had been previously called, was in generally good shape and what upgrades were needed—for example, replacing the deteriorated outer cladding—weren’t outside the realm of feasibility. Blueprints shown to them by the son of the original owners gave them the confidence to make the necessary interventions. It was a buy.

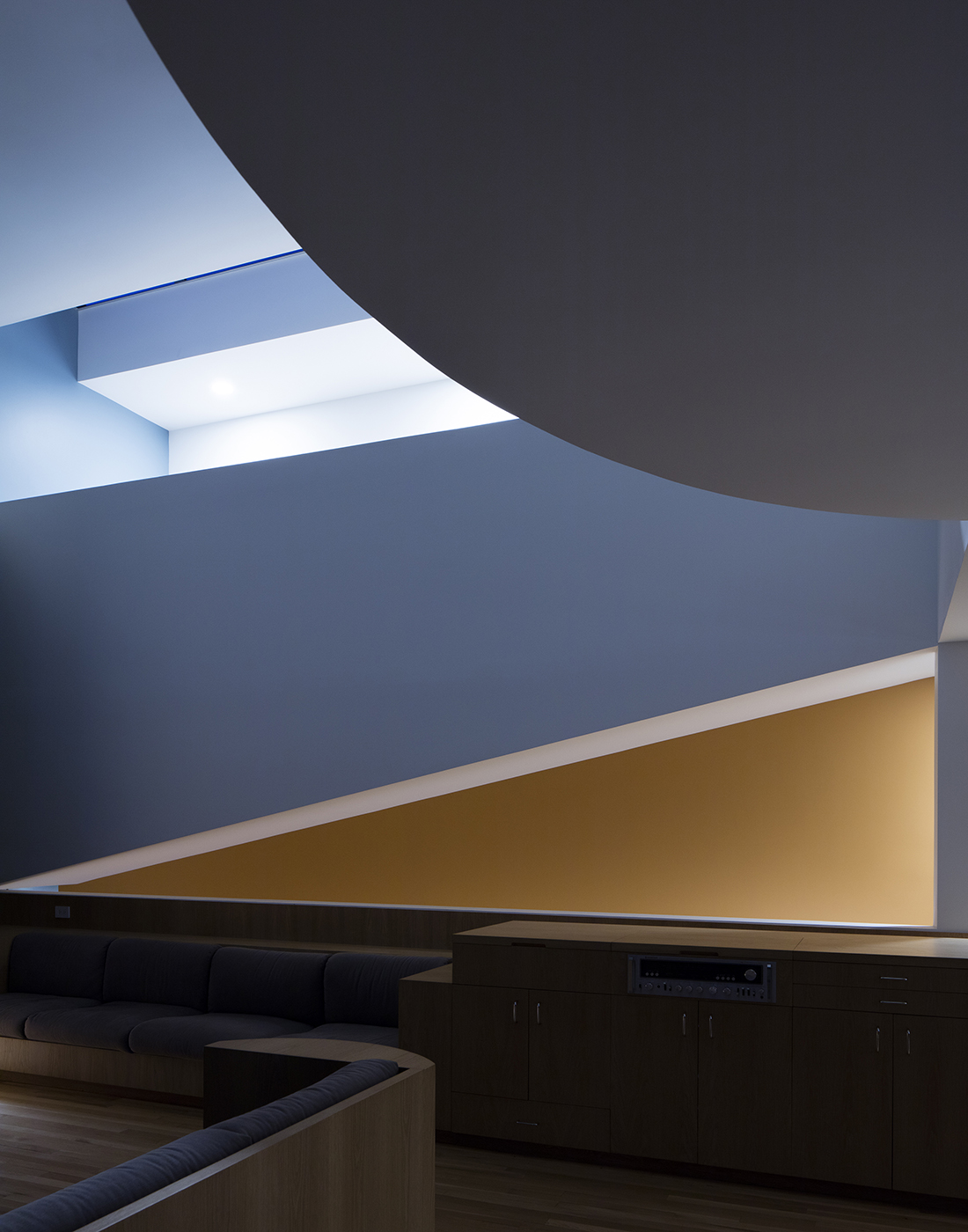

In contrast with Gwathmey’s debut—a fairly compact, cuboid dwelling—the Haupt Residence is less reticent about its footprint. Though well-received by the architectural press in its day, the 4,400-square-foot house never developed much of a reputation—unfair, as it has more than a handful of surprises to offer. The half-level section, where stepped ramps link the two main levels (plus a basement), is novel for a Gwathmey home. A living-room reveal at the base of the fireplace shows how mischievous the architect could be when he wasn’t groveling before bankers and art magnates. The pastel color scheme was well-considered, and handrail details that might seem arbitrary do, in fact, find their basis in the plan.

“He had a systematic approach to the detailing, and it gets played throughout. We followed that mantra with the renovation,” Worrell said. At the same time, there were certain elements that seemed to prefigure the postmodern malignancy to come. A capricious millwork piece over the fireplace and an obstructive kitchen built-in “felt editable,” Worrell recalled, and were removed. Also in the kitchen, outdated surfaces, such as the countertop laminate, were replaced with more durable stuff and new appliances—in matching white-oak tones—brought in. The terra-cotta flooring, laid out with an unfortunately wide grout, was ripped out for something more contemporary: an antibacterial tile, which the marketing materials say has a “concrete effect.”

When it came to the main bathroom upstairs, Worrell and Yeung were somewhat bolder. They overhauled the space, bringing in Italian tiles, an oversized bathtub, and new casework, which, it should be said, echoes the retained built-ins in the living room.

“It was preservationist in spirit, but not everything was meticulously restored,” Yeung said of the project parameters. “Someone who respects the architecture of that era wouldn’t necessarily come to the conclusion that we changed a lot of things. What they will notice is how fresh it all feels.”

This past summer, the new owners, having decided to relocate to Hawaii, sold the house for $9.25 million. But for the architects, the experience brought deeper lessons. For Yeung, the protracted renovation (it was split into two phases) reinforced his conviction that a minimal yet purposive material palette can have just as much of an impact as form. Meanwhile, Worrell found that starting from a strong conceptual footing can also pay dividends. “We always try to start out with a strong idea that can inform even the most minute details. It helps to formalize decisions and keeps a strong aesthetic throughout,” he said. “It also keeps you from being overly original, and that’s a trope of modernism we still respect.”

Header image: The Haupt Residence is notable for its half-level section and subtle paint scheme. (Naho Kubota)