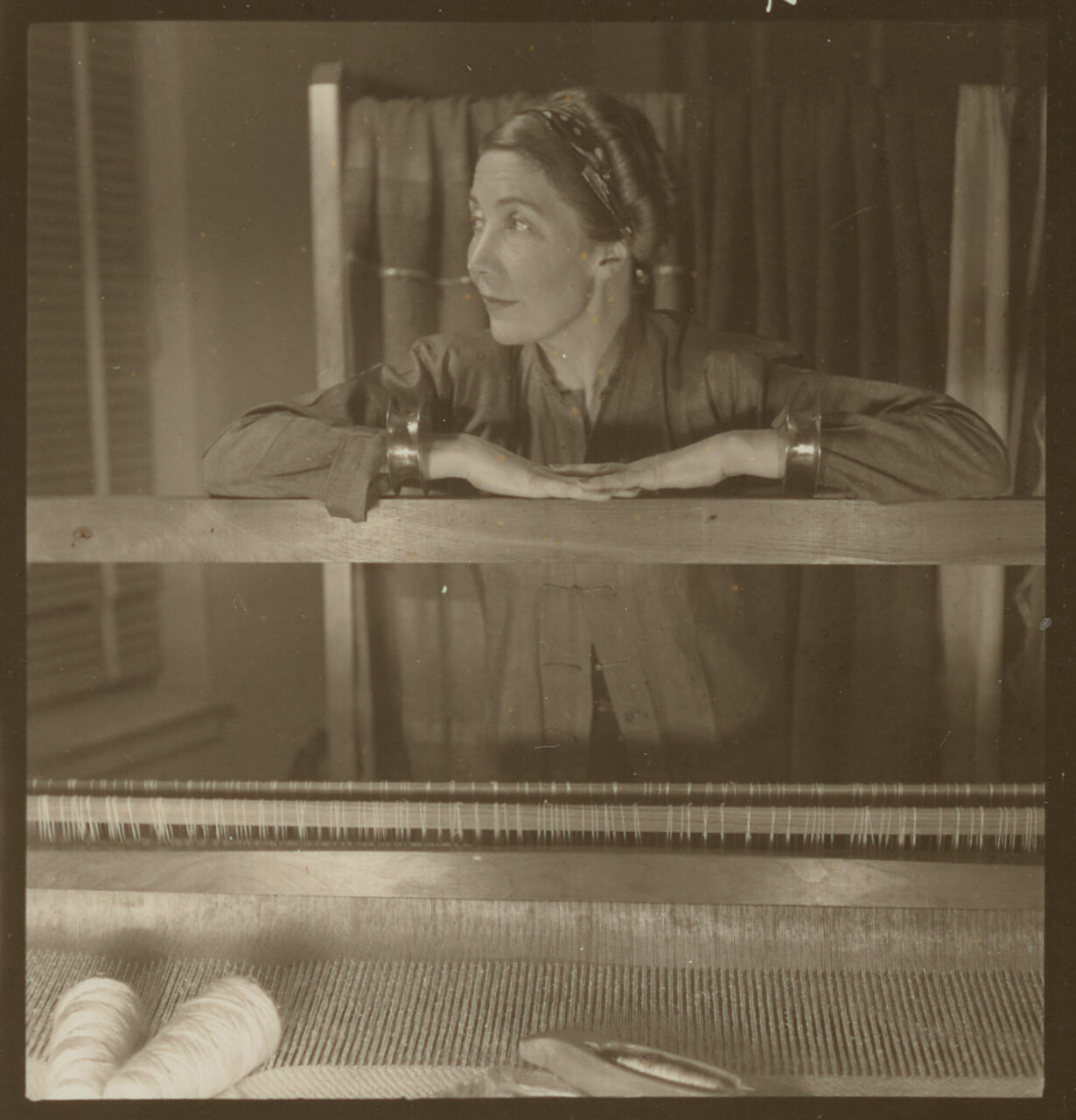

Ascending the regal staircase of what was once Andrew Carnegie’s mansion, I fear for a moment I may be trespassing in an affluent Upper East Sider’s residence. But upstairs the dimly lit halls are quiet, lined with samples of curtains and clothing, glinting behind glass. A little red loom sits alone in a room.

The second floor of New York’s Cooper Hewitt Museum hosts A Dark, a Light, a Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes, the first retrospective of the iconic midcentury textile artist and entrepreneur.

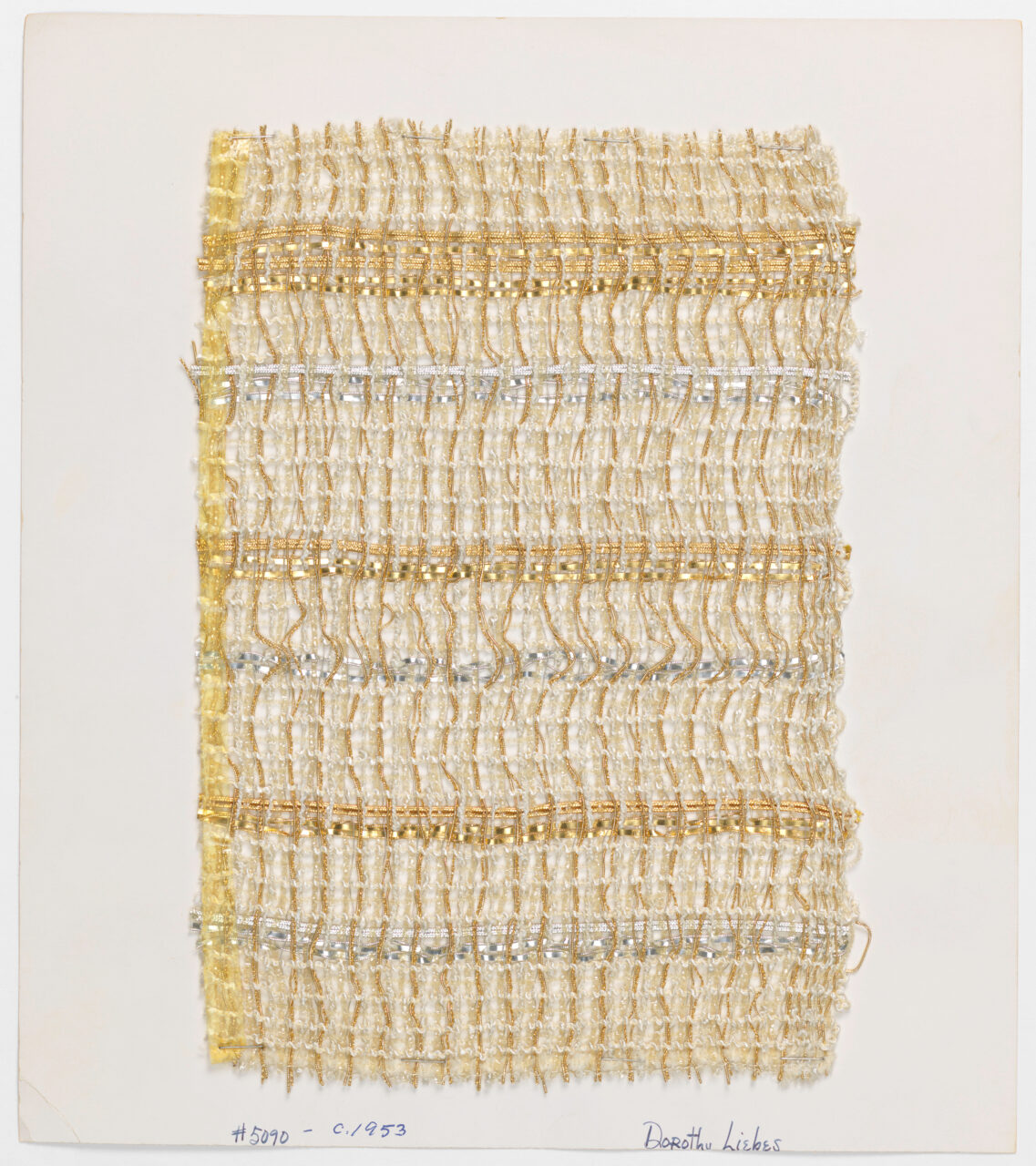

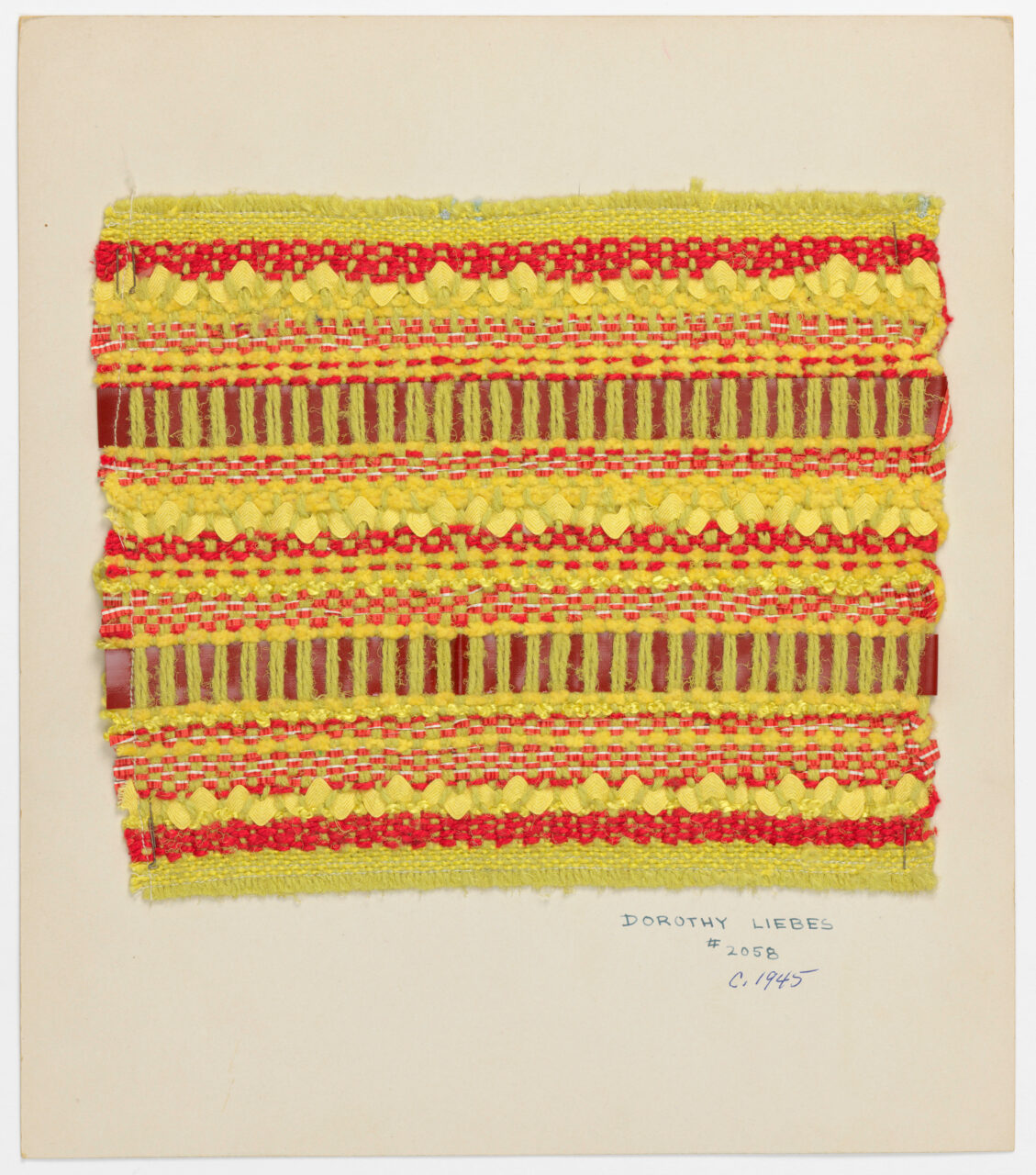

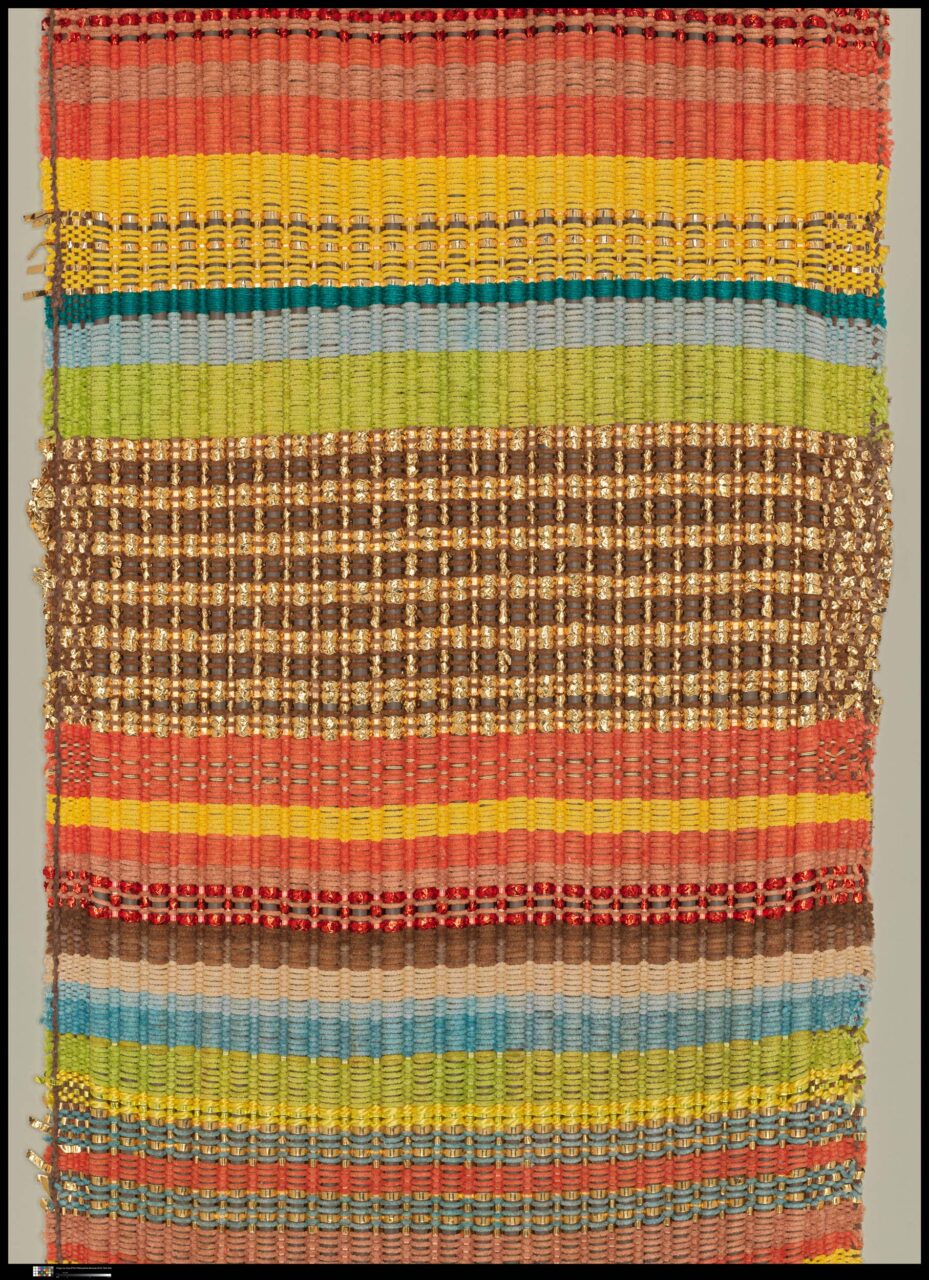

Wandering through the quiet aisles, I peer into the folds of tall, shimmering drapes, scouring the edges of fabrics for a confession. My gaze follows reeds and fibers across the material, arriving at a hodgepodge of contrasting textures. The work’s impressive effect is the result of an intricate network of aesthetic and technical decisions. Frays and folds illuminate the delicate patterns by which textiles shape a room, a body, an era. On view until February 4, the exhibition is a Lurex-gilded gateway to the transformative power of textiles.

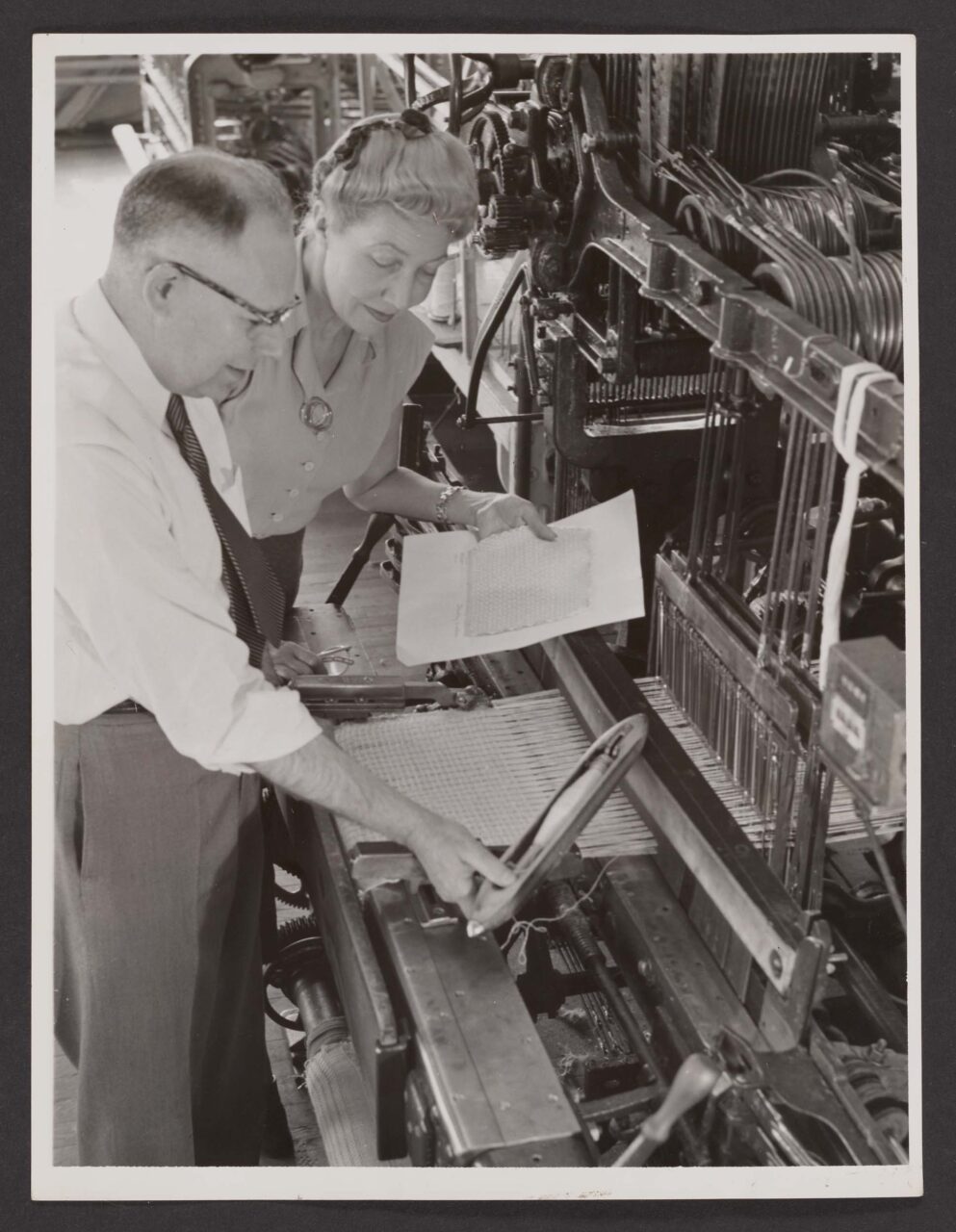

Throughout her career, Liebes was commissioned to create fabrics and upholstery for a multitude of opulent settings. These included the dramatic red drapes of the Waldorf Astoria’s Marco Polo club and the silver curtains that frame Lucille Ball in Lover Come Back. She designed for prolific architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and garment makers like Bonnie Cashin. But she consistently leveraged her tastemaker status to generate more affordable and widely accessible reproductions of her work.

As a pre-internet influencer, Liebes worked as celebrity ambassador across luxury and mass-produced markets. In partnership with Lurex, she created a plethora of materials showcasing the brand’s metallic threads. One piece, a bronze drape that adorned the walls of a bank’s boardroom was made to shine like polished pennies.

Since the Industrial Revolution bore the technology to mass-produce synthetic fibers, reproductions have allowed those with less to embody an illusion of wealth. All of this came under the guise of accessible self-expression. In a 1963 commercial, Liebes stands before her wall of yarn, claiming thanks to “the wonderful new Prestige Nylon from Dupont… there are new ways to express yourself in the fabrics you choose.” An issue of Collier’s Weekly from April 1946 dubs Liebes “A Weaver of Dreams.” I might call her a polisher of pennies.

The reproduction of plastic glamor has unfortunately resulted in dire environmental consequences, and while Liebes’s legacy is not exempt from the evils of industry, it’s also rich with the tradition of weaving’s communal spirit. In images of Liebes’s weaving studios in San Francisco and New York, craftspeople sit along either side of a large loom and lend us a feeling of this convivial atmosphere. Her studio in San Francisco’s Chinatown strived to integrate the local community through hiring and educational offerings. Many women who worked and studied with her, including Mary Walker Philips, championed textiles as fine art.

The curatorial text attributes Liebes’s work to “visual interest” patterns that pique the Western eye. Yet the “clashing colors” she became known for—close chromatic combinations like blue and green or pink and orange—visually evoke the bright palettes of Latin American textiles. Seventeenth century texts describe Inca rulers wearing tunics of blue, white, and green. There are also records of red and pink ensembles. Garments were likely colored with natural dyes like indigo and cochineal, a parasitic cactus-eater native to tropical and subtropical regions of South and North America. Unique color codes communicated social class before forced assimilation to colonial dress contributed to the suppression of cultural symbols.

A “house apron” on display mimics patterns of traditional enredos; a material titled “Mexican Plaid” could use additional context. While the exhibit offers a thorough investigation into Liebes’s legacy, I left inspired to uncover the roots of her stylistic influences.

Delving into creative influences whose cultures have been overlooked is at the heart of the philosophy that drives historic textile studies. This retrospective inspires one to explore these nuances of representation. We’re searching for the threads that bind together histories and movements at the edges of the fabric.