What town halls are—their names, their forms, their programs—and the way they relate to the public and the city have changed dramatically over the centuries. Each new incarnation evolves from the last, building up a rich legacy full of successes and lessons that can be brought forward into future manifestations.

In Britain, the 1800s were an era of dramatic change, tumultuous growth, vigor, and pride for British cities, all of which was anchored and guided by the Victorian Town Hall. The typology’s eloquent facades spoke of civic pride, communal purpose, economic strength, and artistic verve. Their interiors contained multipurpose halls, whose size and opulence made Buckingham Palace seem twee and quaint.

After World War II, in a national equivalent of the pioneering reforms of the great liberal mayors of the 19th century, gone were the vast republican Roman temples competing with the beautiful behemoths of British neo-baroque, the people-palaces of competing virtual city-states. In their place came modernity, a universal design language that spoke of a shared future and universal values.

As globalization, deregulation, and the European dream reached their respective zeniths in the 2000s under New Labour, architecture once again took on a starring role in the perpetual transformation of our cities. Private capital mingled with state funding to deliver colorful new spaces that mixed consumption and education, profit and provision, in an apotheosis of a historical compromise between society and the market.

We are living through what is perceived to be one of our democracy’s most intense crises in generations, which means it is in fact the perfect moment to build monuments to its rebirth. In crisis lies the greatest opportunity for reinvention. In each island of progress may there rise democratic monuments of symbolic sustenance and practical pageantry, for our sprawling cities, for our expanding towns, for the many and for the few; beauty, but for everyone.

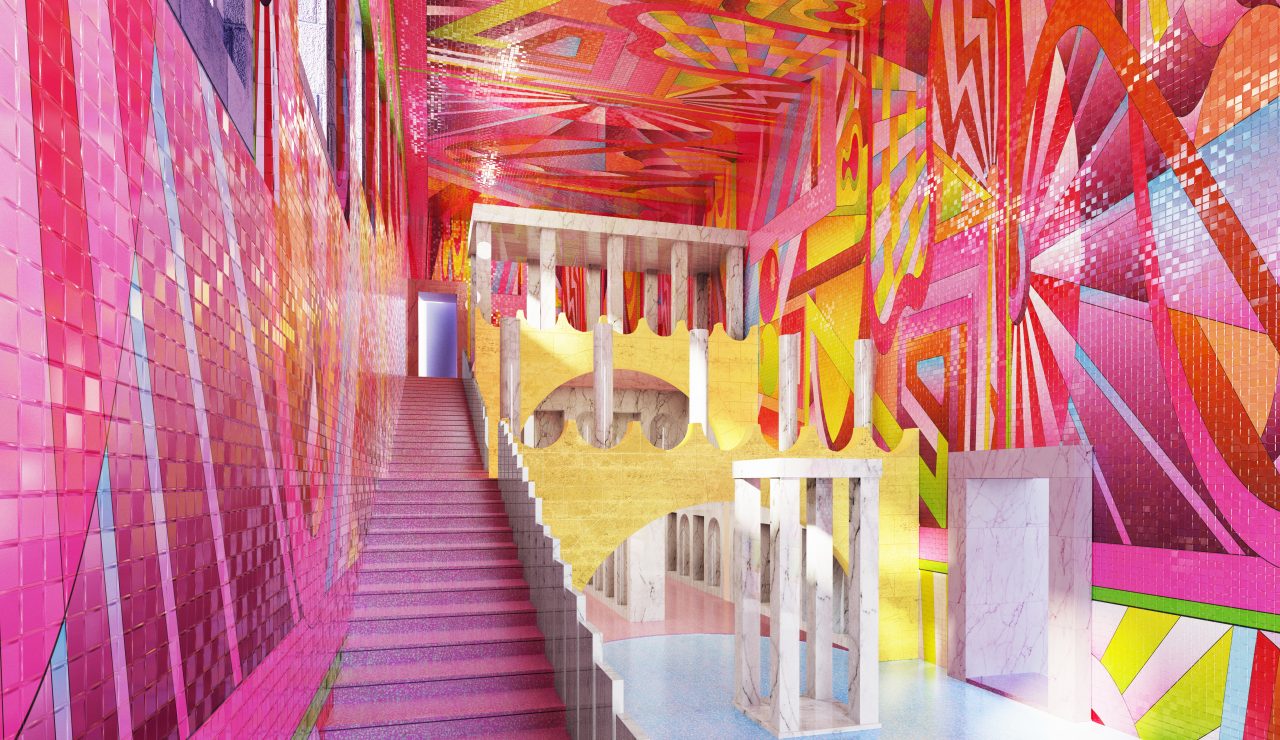

It is time for the Town Hall as a democratic monument: architectural plurality in compositional unity. Architecture can be eloquent, and in using color and richly saturated materials, we can create buildings that embody us, our collective dreams, and our sense of communal identity. A democratic monument’s public face is proposed to be a large civic facade, designed in a contemporary manner, but echoing older structures—such as our Gothic Cathedrals—in its forthright form and ornamental exuberance. Encrusted in richly colored and patterned tiles, manufactured using the latest digital ceramic technologies, and designed by local artists, it presents a proud, joyfully new beacon of confidence to its city.

The next incarnation of the Town Hall is to be a monumental embodiment of our evolving liberal democracy as it moves into another new phase of energetic activity and robust invention. One in which architectural language and expression can both embody and reconcile the perpetual tensions between market and state, and minority and majority. One in which a fragmenting society and a diffuse urban realm are given new symbolic anchors that neither ignore the deep veins of difference, nor impose an arbitrary uniformity, but celebrate the constant tensions, debates, and engagement that keep any one aspect of society from eclipsing the others.

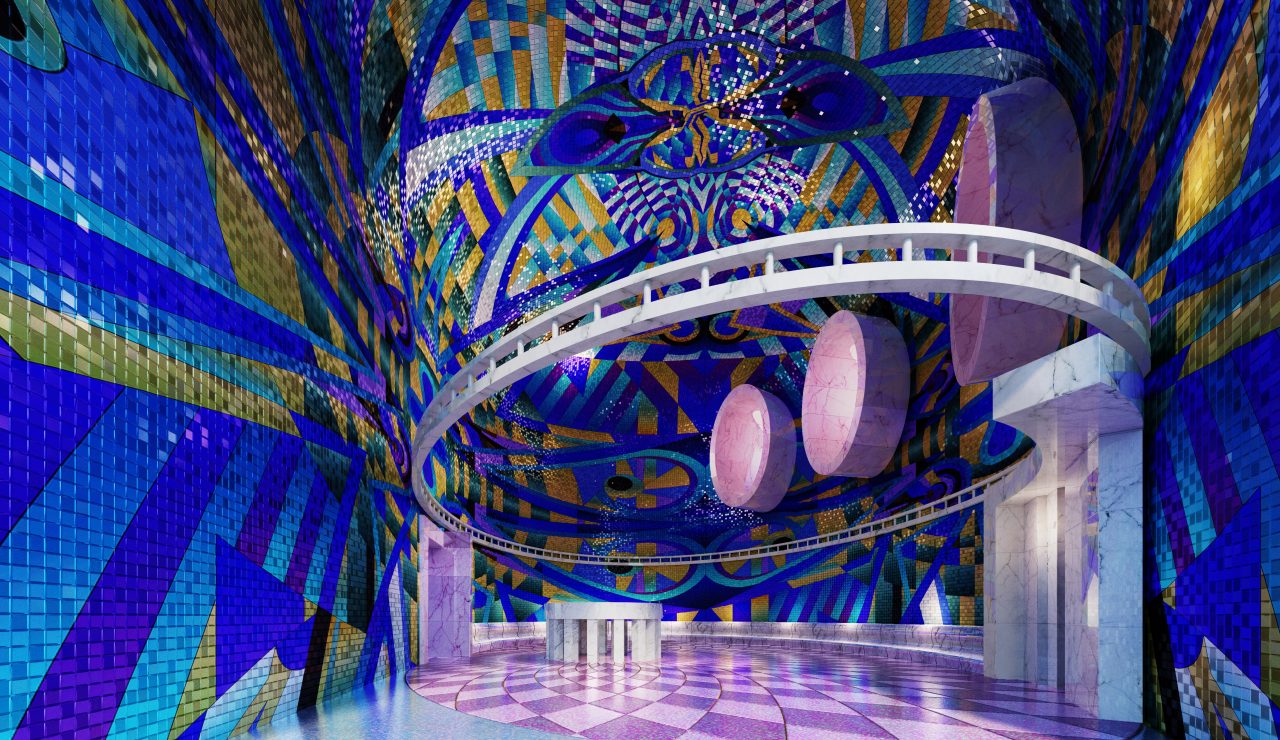

Council leaders and mayors will time-share the same halls of state with LGBT groups, unions, trade bodies, music festivals, and faith events, all within interiors that make the shopping centers of a generation before seem dull and meaningless.

Civic interiors in which durable, permanent, chromatically vivid decoration will be brought back into public architecture. The bright nothingness of white paint and alu panels will no longer be the default noncolor, but rather all the hues we love so much in nature and art will be deployed to once again fill our city halls and collective interiors. Digital decal ceramic printing of large decorative schemes will fill entire volumes in combination with varied translucent glazes, will create rooms that glitter and glow. The glazed tiles will reflect the changing weather outside and the activities inside, suffusing the internal atmosphere with a strong and distinct sense of place, a potent color-filled “somewhere,” rather than a white “anywhere.” Expensive marbles will be placed next to pink and baby blue terrazzo, as well as next to cheap, but robust, laminates in lemon yellow and orange, green plastics and lavender powder-coated steel, while glazed tiles will meet ochre travertine and puce anodized aluminum.

A vision of public space that uplifts and embraces through ornament, materials, and color.