The following essay us an excerpt for the book, Solid Objective… Order, Edge, Aura, published in 2017 by Lars Muller Publishers.

The design of interiors has come to embody a line of egocentric thoughts. It purports to put our biological body—and possibly even our soul and individualistic existence—at its center. Womb-like sensations arise, promising warmth, safety, and other prenatal comforts. How do we sufficiently swaddle or cushion the self for it to survive our savage reality? The interior becomes a pure haven for the spirit, something that seems increasingly public. We create mobile cocoons, shielding ourselves with screens, headsets, and blank stares. We eschew or minimize contact with others. Absurdly, even though technology has seemingly brought the outside world in, our devices have diminished points of contact with it. The public realm is contained, compressed, and trapped behind thinner and thinner layers of glass. The exterior is powered up or down with the swipe of a finger.

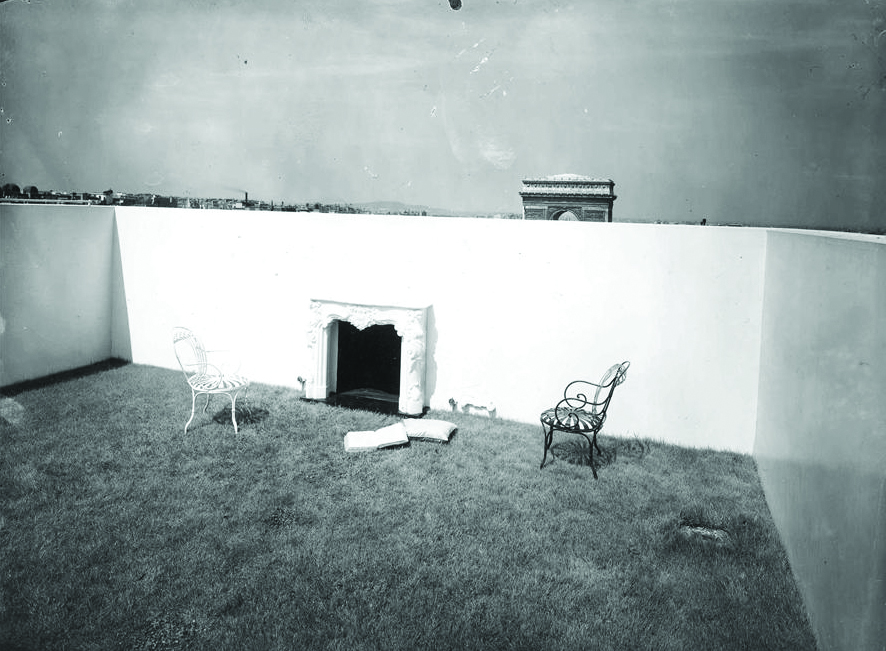

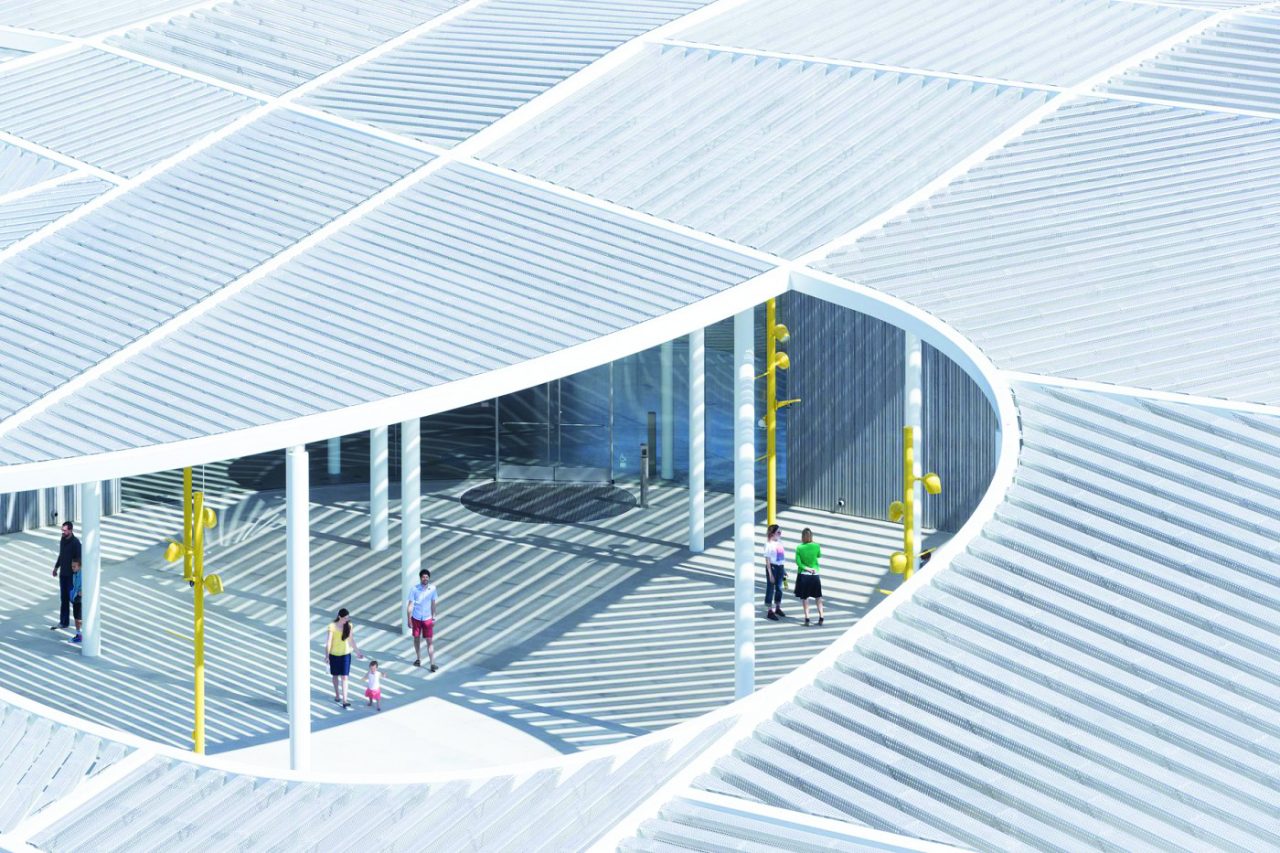

While this notion of interior design evokes thoughts of monastic disconnection, of dwelling in a shielded totality, we would like to consider its opposite: the interior as a locus for a new collective condition, an inside that fosters exchange. After all, it is mostly in the perceived comfort of our interiors that we let our guards down and allow for connections to occur. Up until modernity, humanity experienced its interiors—even those of the dwelling—as a public domain. The living room was a place for conflict and exchange. Even our beds were shared. Given this, let us regard the interior not as a space created by protective surfaces and moods, but rather as a porous field defined by realms and structures. Otherness will trickle in and a productive contamination will ensue.

Beyond mere spatial definition, a new exchange must be fueled by content. This collective interior demands activation by things: Volumes and objects, elements that supersede their functional obligations to play suggestive and symbolic roles—think of the Kaaba, the Butsudan, the kitchen table, and the parliamentary mace. We see this as the vivid place that sociologist Bruno Latour depicts wherein “each object gathers around itself a different assembly of relevant parties. Each object triggers new occasions to passionately differ and dispute. Each object may also offer new ways of achieving closure without having to agree on much else.”[1] In the place of comfort, the new interior instead offers devices of contestation and the promise of an active public.

In order to accommodate differences, an architecture of the interior will be assembled with characterful structures and objects that trigger discursivities, to fuel the fire, the textures taking on qualities of the outside, rupturing and destabilizing. Think of sublime volumes, endless depths, infinity pools, and fillets. Think of Andrei Tarkovsky, the rain inside, cobblestones in the living room, sand in the bathtub.

The interior as a space of contestation might recoup some of the scope architecture has forfeited to the creators of soothing mood boards and Pinterest pin boards. As layered and fleeting realities of the exterior return indoors, condensed and redirected, they might unsettle the insulated, comfortable individual in pursuit of a more vital collective interiority.

Main Image: In Weelde Siet Tot, (In Luxury, Look Out) was painted by the Dutch artist Jan Steen in 1663. The painting warns against degeneration via complacency in the household. The housewife has fallen asleep while chaos fills the home: A boy smokes a pipe, a pig drinks from the beer tap, and the family engages in general debauchery. (Wikimedia Commons)